Brilliant Boards

Pyeonaek Signboards Offer

a Glimpse into the Minds of a People

WRITTEN BY

Tim Alper

contributing writer

Often overlooked by visitors to temples and other buildings, pyeonaek are wooden boards decorated with stunning calligraphy. Deciphering them can often provide insight into the intentions and desires of the people who created them.

Visiting a Korean temple is a veritable feast for the senses―at times it can seem that there is simply too much to take in during a single visit: With the sound of monks chanting, wind chimes and the beat of wooden bells filling your ears and the powerful smell of incense in your nostrils, you could be forgiven for missing some of the most subtle and interesting sights of all. Surprisingly, perhaps, some of these can actually be found before you even set foot in the temple.

On the wooden gates you usually need to pass through in order to gain access to the front of the temple, you will often find a board decorated with Chinese characters (usually three, but sometimes four or five). Unless you are a student of hanja(Korean Chinese characters), these can often be hard to decipher. Upon seeing these, you might be tempted to ask a Korean what they mean. Interestingly perhaps, you could be surprised by their answer.

In some cases, these boards, known as pyeonaek, are made up of easy-to-understand characters, to the extent that a modern middle or high school student could understand them. But in some cases, their meanings are so steeped in esoteric nuance and poetic imagery that even a professor of literature would be stumped if asked to explain what they mean.

Although these signs are almost ubiquitous in temples, in preindustrial age Korea, they were also commonplace outside many other buildings. Some august offices, former royal palaces and government buildings are also adorned with pyeonaek boards. Often, these boards have fascinating stories―and a few were even created by kings.

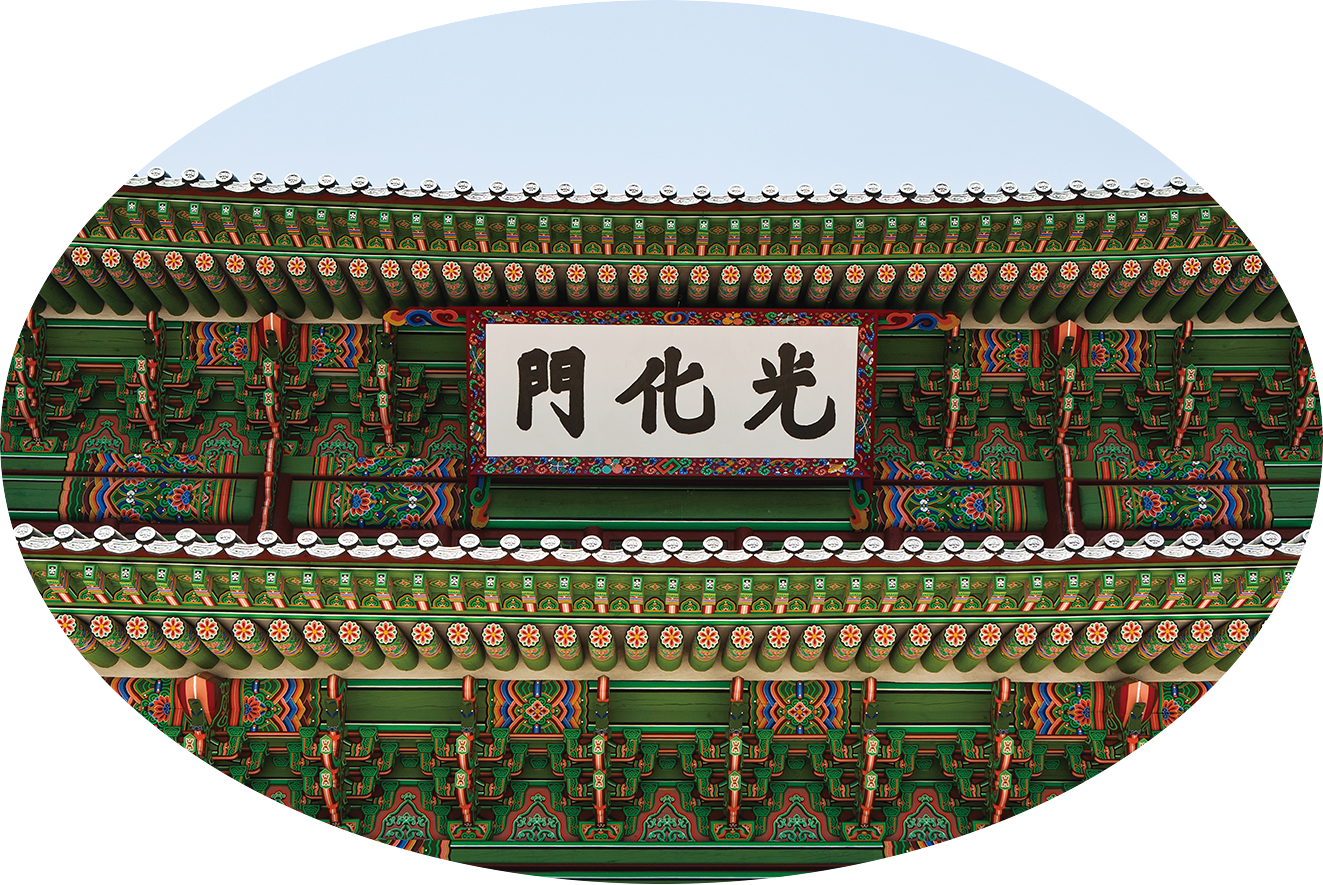

The pyeonaek of Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Gate was restored in2010.

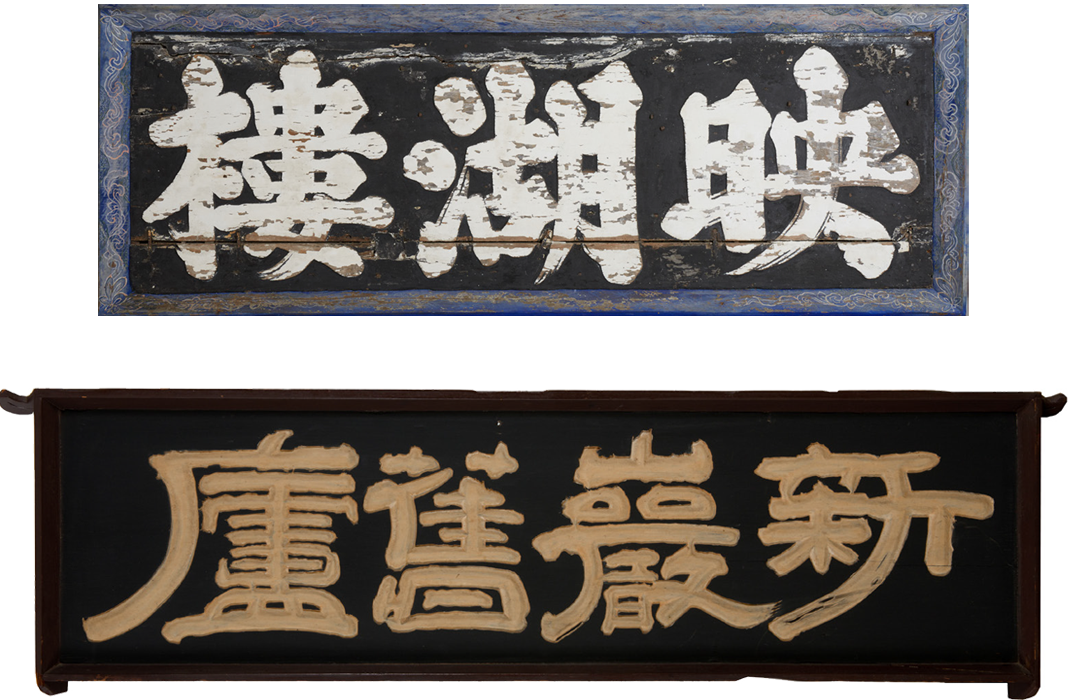

A new pyeonaek currently in production will feature gold writing on a black background, based on historical evidence. ©clipartkorea

Calligraphic Charms

Historians cannot say with any certainty exactly when the tradition of creating pyeonaek first came into being in Korea. But the consensus of scholarly thought is that they emerged during the Three Kingdoms Era (from the First Century BCE to the 660s CE), a time marked by a massive cultural exchange with nearby countries such as China.

By the Unified Silla period (668-935), the tradition was commonplace and the finest calligraphers in the land were often sought out to create pyeonaek pieces. A few of these pieces are still extant, including two notable works by arguably the finest calligrapher of his age: Kim Saeng (711-c.), who made pieces for the Mahavira Hall at Gongju’s Magoksa Temple and a piece for the Baengnyeonsa Temple in Gangjin.

In the historic city of Andong, you can even see a work by King Gongmin of Goryeo, a mid-14th century ruler who had a passion for calligraphy.

Although the exact meaning of some pyeonaek items is lost to time, in some cases, their meaning is straightforward and even descriptive, simply stating what a building’s purpose was. But in other cases, they were intended to encapsulate values held dear by the people who constructed or owned the building.

While you would almost never have found pyeonaek on the dwellings inhabited by ordinary folk, who simply could not afford to pay calligraphers or lacked the education needed to create their own boards, they were once common on the family homes of the wealthy, who liked to display statements about their―or their ancestors’―moral or religious values on their homes.

The tombs or burial grounds of the rich often featured similarly bookish or pious messages, while schools and other educational facilities featured statements about the value of learning.

Sometimes, however, pyeonaek meanings are more mundane, containing observations about local topography. In some cases, they make reference to pungsu(geomancy). For instance, at Seoul’s Namdaemun, a gate on the old city walls, the pyeonaek is displayed vertically instead of horizontally in an effort to counter the frighteningly large amount of “fire energy” naturally found at the site.

Every pyeonaek is unique, featuring different fonts, border designs and text colors.

Spirit of the Times

If the Three Kingdoms era saw the birth of the pyeonaek tradition and the Unified Silla period saw its popularity spread, the Goreyo era (918-1392) was marked by a time of piety, during which Buddhist temples sprung up all over the country. Almost all of these were adorned with fine pyeonaek pieces, often containing faith-related statements.

But the Joseon rulers, who seized power in 1392 and held onto it until the 20th century, eschewed Buddhism. The golden age of religious pyeonaek came to an abrupt end. However, the Joseon elite were scholars, who found a new use for pyeonaek, using them to decorate the entrances of their academies. At larger academies, which featured multiple classrooms, libraries and shrines, each individual building often had its own pyeonaek―all making reference to the scholar’s austere and high-minded philosophical values.

Today, pyeonaek are harder to find than they once were. But Koreans still cherish them wherever they find them―and learning more about pyeonaek can be a fascinating way to delve a little deeper into a lesser-known side of Korean history and culture.

A signboard written in Korea’s indigenous alphabet, Hangeul, hangs above the entrance of Seoul’s Namsangol Hanok Village. ©clipartkorea

Other Articles

-

Special Ⅰ Linking Time and Space

-

Special Ⅱ Day Trip to a Flag Station

-

Trend Tasty Stations

-

Hidden View Electric Night

-

Interview Pianist Jae Hong Park

-

Art of Detail Brilliant Boards

-

Film & TV Hellbound

-

Collaboration Gucci Gaok

-

Current Korea Korea Reinvigorates Bilateral Ties

-

Global Korea Museum Night:Korean Cultural Center Opens at Night