Contents

Flowers at Suncheon Bay

Artistic Director of Dance Makes Modern Dance like Live Film

Quilting Squares of Tolerance

2018 Inter-Korean Summit

Bojagi,

Quilting Squares of Tolerance

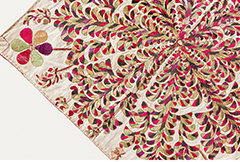

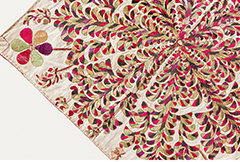

Although it’s now a precious handicraft product displayed in galleries and museums, the traditional bojagi wrapping cloth and quilting square used to be part of people's daily lives. All women used to stitch bojagi by hand, regardless of their social status. They used the cloth squares as canvas, using scrap pieces of fabric to make geometric patterns. From small objects to the toil of these women and their love for their families, bojagi stretched and grew to hold everything and anything.

Written by Lee Eun-yi , designer & writer Photos courtesy of The Museum of Korean Embroidery

The Square that Can Cover Anything

Bojagi cloth squares used to be daily accessories widely used in Joseon times (1392-1910). All women, the nobility or commoners alike, made their own bojagi. They took pieces of square fabric, usually cotton or silk, and decorated them with embroidery, or made patchwork bojagi from scraps left over after making clothes for their families. While the square pieces of fabric were used to wrap objects like clothing, blankets or folding screens for transport, they also had a wider variety of uses, such as covering the table, carrying some laundry or packing wedding presents. They were also used as bags before today’s bags became widely available.

The practicality and compactness of the bojagi are its greatest strengths. It can wrap and cover anything, regardless of shape. It changes its own shape to fit the object it’s covering, and then returns to its square form after use. Lee Eo-ryeong uses the bojagi and the bag as metaphors to highlight the differences between East Asian and the Western philosophy. The bag, which fits objects into a fixed space, represents the rationality-based West, while the bojagi, which wraps itself fluidly around any shape for any use, represents the decentralized nature of the East.

Bojagi Embraces Life

The reason why bojagi are widely recognized as an art form, displayed in galleries and museums, lies in their design. The embroidery is simple and modern in aesthetic, comprising simplified forms of flora and fauna, such as flowers, trees, butterflies and birds. Then there is the patchwork bojagi made of scrap fabric, the compositions and harmony of which have been compared to the abstract art of Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee or Wassily Kandinsky. The contrast of primary colors and the mix of neutral tones show a sophisticated and unique use of color.

Bojagi researcher Heo Dong-hwa, who established the Museum of Korean Embroidery in 1976 with a collection of traditional handicrafts, has introduced the bojagi to 55 countries worldwide, including in the U.K., the U.S., Australia and New Zealand. Heo proudly praises the bojagi in the international press, keeping many copies of the articles in his scrapbook. He brings truth to the saying that, “What’s most Korean is that which is most universal.” It must have been universal maternal love contained in a square of cloth that moved hearts all over the world. The life of a mother -- the hardship of giving birth in the household, the longing she feels for her parents and brothers, her oppression in a patriarchal society, and the love she feels for her family -- is sublimated in the beauty that is contained in the all-encompassing tolerance of the bojagi.

Other Articles

Flowers at Suncheon Bay

Artistic Director of Dance Makes Modern Dance like Live Film

Quilting Squares of Tolerance

2018 Inter-Korean Summit

Application of subscription

Sign upReaders’ Comments

GoThe event winners

Go

May 2018

May 2018