Contents

Flowers at Suncheon Bay

Artistic Director of Dance Makes Modern Dance like Live Film

Quilting Squares of Tolerance

2018 Inter-Korean Summit

Korean Festivals

Setting the Stage for Cultural Restoration and Reconciliation

“The constant pressure to move toward economic wealth, social status and privileged power has persisted for too long. It is now time to take an interest in the positive effects of leisure and in the happiness that will result from participating in festivals; in the celebration of mutual growth and diversity.”

Written by Ryoo Jeung-ah, Senior Researcher of Korea Culture & Tourism Institute

Tracing the 2,200-year History of Korean Festivals

Korean festivals are largely based on rituals in ancient times such as the Dongmaeng during Goguryeo (37 B.C.-A.D. 668) (고구려, 高句麗), the Yeonggo during Buyeo (100s B.C.-A.D. 494) (부여, 夫餘) or the Mucheon during Dongye (200s B.C.-A.D. 400s) (동예, 東濊). Similar to seasonal thanksgiving festivals, they were held as expressions of gratitude for the harvest. The oldest historical text about such Northeast Asian traditions can be found in the “Eastern Barbarians” chapter in the “Book of Wei,” part of the “Records of the Three Kingdoms” (A.D. 200s) (삼국지, 三國志). That Chinese history book contains an extensive description of harvest ceremonies, and songs and dances from that age, when religion was intimately connected with the arts and politics. In those days, festivals were the culmination of certain ideals. They were activities that maintained harmony between nature, the arts and humanity. Today, these traditions live on in the form of widely celebrated events, like the Gangneung Danoje Festival and the Chuseok Mid-Autumn Festival.

A Buddhist ritual called Palgwanhoe was first held during Silla ( 57 B.C.-A.D. 935) (신라, 新羅). This festival continued as a form of thanks-giving during Goryeo (918-1392) (고려, 高麗), intended to strengthen ties among the ruling classes. Meanwhile, commoners bonded through the Lantern Festival. During Joseon (1392-1910) (조선, 朝鮮), the lower classes contributed to the development of the performing arts, such as tightrope walking, acrobatics, witticism and musical performances. One difference from past kingdoms was the clear distinction between actors and spectators. The theater lost its standing and fell into a long period of decline because of the difference. For the common people, village rituals were the only tangible reminder of these festivals. They relied on rituals, such as the dodanggut, the byeolsingut, the danogut or the dongje for a sense of community. They developed traditional mask dances, or talchum, to put elements of the theater. Mask dances were a form of satire directed at the ruling classes.

Restoring the Value of Festivals and Promoting Reconciliation

Confucianism during late Joseon devalued the importance of the theater, contrasting it to the aristocracy. Naturally, the theater was perceived as undesirable and tasteless. Long periods of cultural distortion, war and economic reconstruction resulted in a high regard for labor. Survival was of the highest priority. It took some time for people to realize that the theater was just as important as making a living, and that plays could be a new source of bread and butter. The Seoul 1988 Olympic Games, one of the first events to boost modern Korea’s international presence, helped to raise awareness of the significance of festivals.

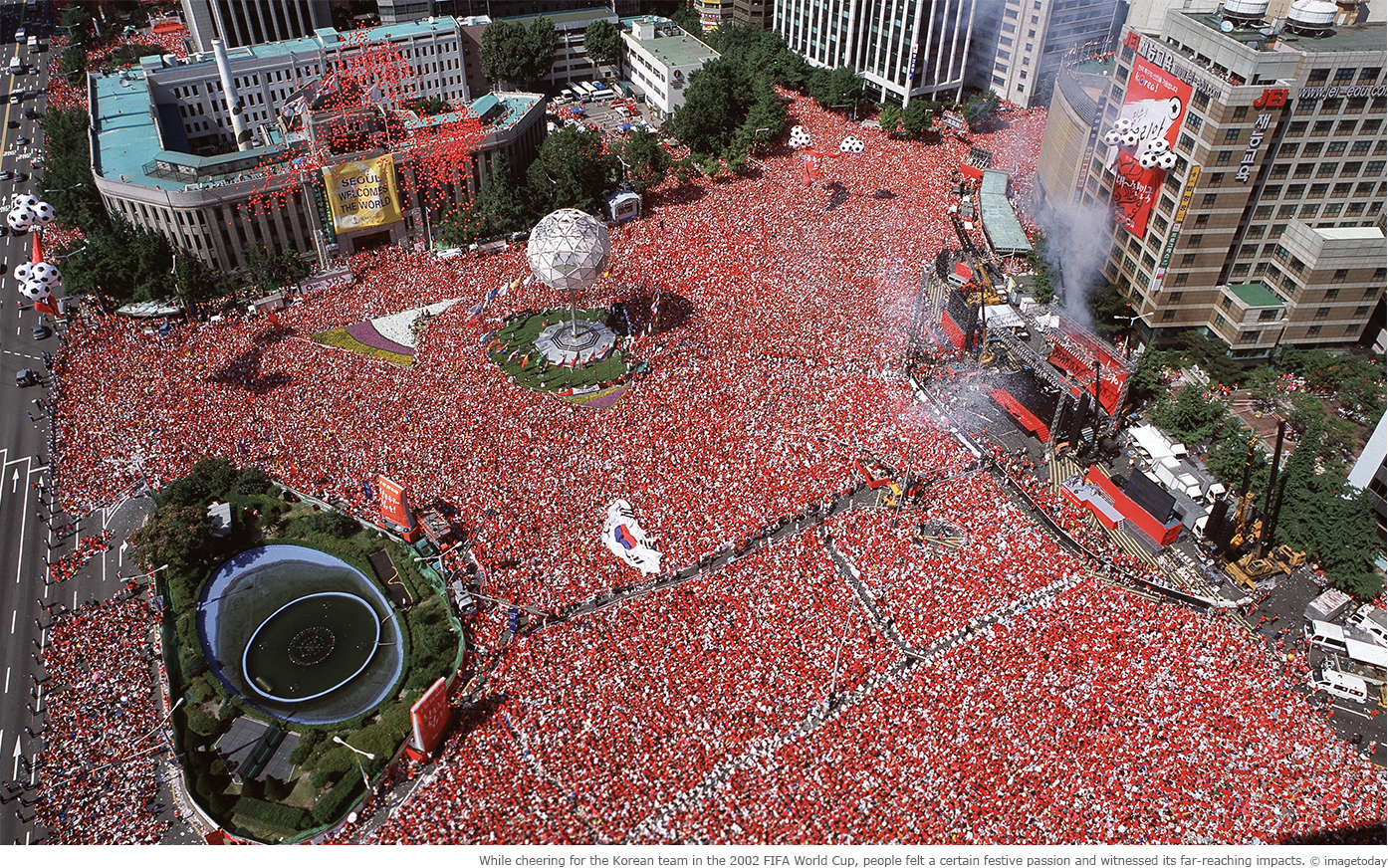

While cheering for the Korean team in the 2002 FIFA World Cup, people felt a certain festive passion and witnessed its far-reaching impacts. The international football/ soccer festival was a magical halt to reality, and people formed strong ties with one another simply by rooting for the same team. As part of the Korean team’s supporters club, people reaffirmed their national identity and developed a sense of pride. Another recent “festival” was the 2016 Candlelight Revolution, a weekly million-strong vigil staged by democracy activists and bringing together all tiers of society in protest against a political scandal involving the now-impeached former president. It served as a valuable opportunity for people to reflect on their political consciousness and to stand up against corruption and influence peddling. The movement was an indicator of not only political change, but also of cultural change. It was an expression of people’s longstanding desires after years of suppressed acquiescence.

More than 1,000 Festivals Nationwide

Today, festivals have a more inclusive and broader role. It’s more appropriate to define them as “sacred times during which actions and words usually considered taboo are embraced; times in which differences are acknowledged based on mutual trust; times for action to express a determination to counter vested power structures, inequality, oppression, conflict or darkness.”

Officially, Korea has more than 1,000 festivals every year, many of which reflect peculiar regional characteristics. Some festivals, such as the Gangneung Danoje Festival, the Namwon Chunhyang Festival, the Gijisi Juldarigi Festival and the Andong Mask dance Festival all have a long history, while others are fairly new, ranging from less than a decade old to about 40 years old.

Festivals about traditions and history include: the Gimje Horizon Festival, which celebrates Gimje’s farming and folk traditions; the Andong Mask dance Festival, which has expanded beyond simply the traditional hahoe talnori mask dance performance; the Jinju Namgang Yudeung Festival, during which lanterns carrying the wishes of people float past along the Namgang River; the Baekje Festival, dedicated to the history of the kingdom of Baekje (18 B.C.-A.D. 660) (백제, 百濟); the Tongyeong Hansan Battle Festival, a commemoration of the Battle of Hansan Island (1592); the Suwon Hwaseong Festival, held in remembrance of the filial piety shown by King Jeongjo (1776-1800) (정조, 正祖); and the more modern Yeongam Wangin Festival, which highlights the achievements of Wangin (왕인, 王仁) (c. 400s).

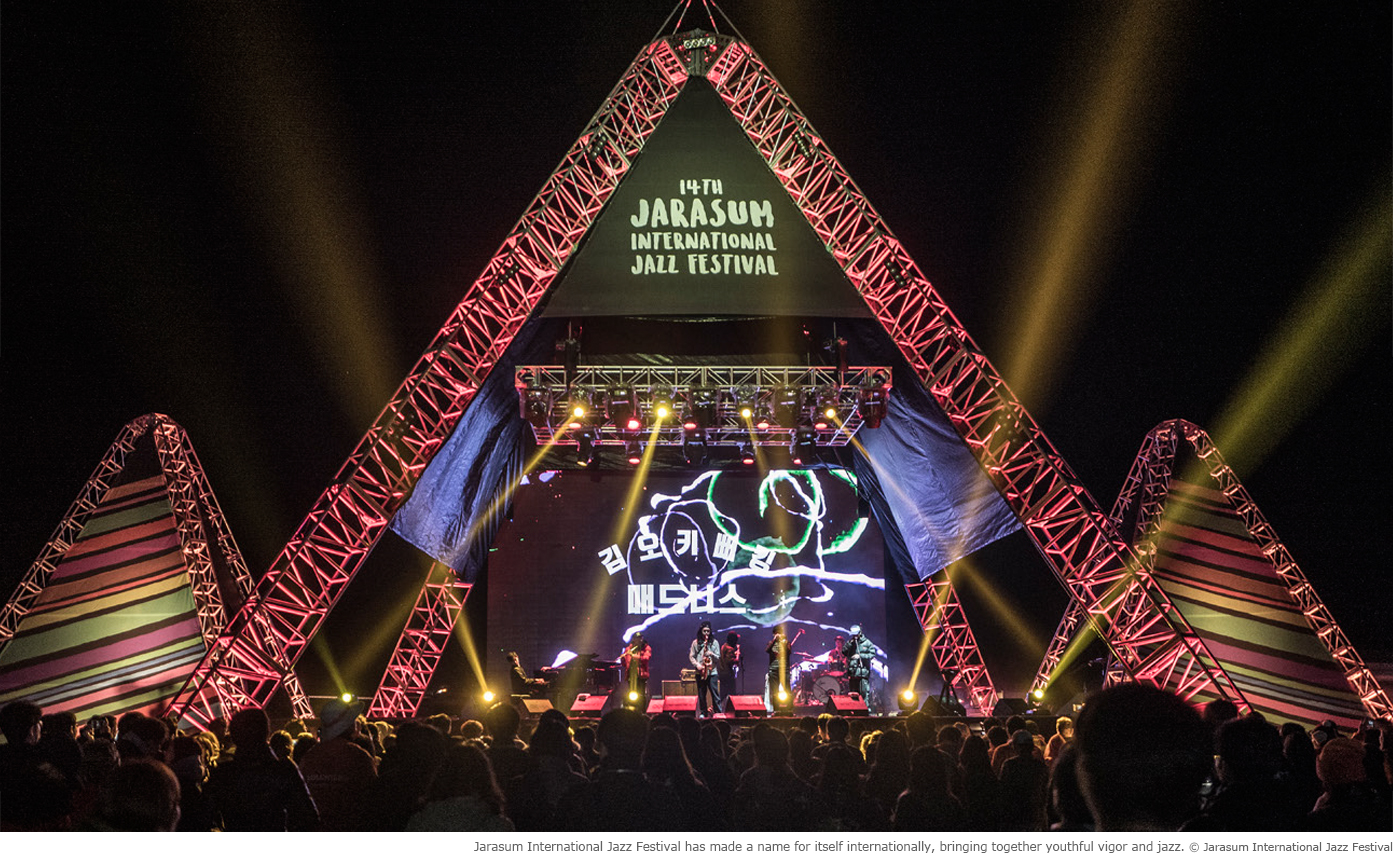

Among festivals about the arts, there are: the Jarasum International Jazz Festival, which enabled the villagers of Gapyeong to familiarize themselves with jazz; the Gangjin Celadon Festival, which promotes the excellence of Goryeo celadon; the Damyang Bamboo Festival, a celebration of the beauty and functionality of bamboo; the Mungyeong Traditional Chasabal Festival, which celebrates traditional ceramics; the Hyoseok Cultural Festival, which commemorates the novel “When Buckwheat Flowers Bloom” (1936) (메밀꽃 필 무렵) by Lee Hyo-seok (1907-1942)(이효석, 李孝石); and, the Chuncheon International Mime Festival, one of the world’s top three mime festivals.

Other festivals are based on natural products or local specialties. You can jump into mud pools at the Boryeong Mud Festival, have a go at ice fishing at the Hwacheon Sancheoneo Ice Festival, learn about medicinal herbs and traditions at the Sancheong Herbal Medicine Festival, watch the burning of the Saebyeol Oreum at the Jeju Fire Festival, get a taste of fermented products at the Sunchang Fermented Food Festival, and gain an appreciation for UNESCO-recognized ramie fabric at the Hansan Ramie Fabric Festival.

The number of festivals across Korea are far too many to list on one small page, but those introduced above are a good place to start.

Rapid Urbanization and Explosive Economic Growth Have Created a Thirst for Traditional Festivals

People have only recently begun to appreciate the leisurely experience of festivals and the value of play. The constant pressure to move toward economic wealth, social status and privileged power has persisted for too long. It is now time to take an interest in the positive effects of leisure and in the happiness that will result from participating in festivals; for the sake of mutual growth and diversity. With individualism deeply rooted in our society, many people question the compatibility of community-based festivals with their modern lives. However, let’s not forget that countries with a rich history of festivals are found in the West, too, which is known to be even more individualistic than other parts of the world.

Human beings do not live alone. They reaffirm their existence by forming relationships with others, and it is human nature to be caring and considerate. The opportunity to share experiences and to exchange opinions with like-minded people across your community is what helps us to sustain an independent life.

The number of festivals in Korea is increasing by the day, with the trend more prominent in smaller villages and towns. It will take some time for the habit of attending festivals to take root, and the process is expected to involve significant trial and error. Nonetheless, people today are better prepared than ever before to enjoy their festivals all across the nation.

Other Articles

Flowers at Suncheon Bay

Artistic Director of Dance Makes Modern Dance like Live Film

Quilting Squares of Tolerance

2018 Inter-Korean Summit

Application of subscription

Sign upReaders’ Comments

GoThe event winners

Go

May 2018

May 2018