Magnificent

Munsal

Discovering the Secrets of Korean Wooden Lattice Door Frames

WRITTEN BY

Tim Alper

contributing writer

Photos courtesy of

National Palace Museum of Korea

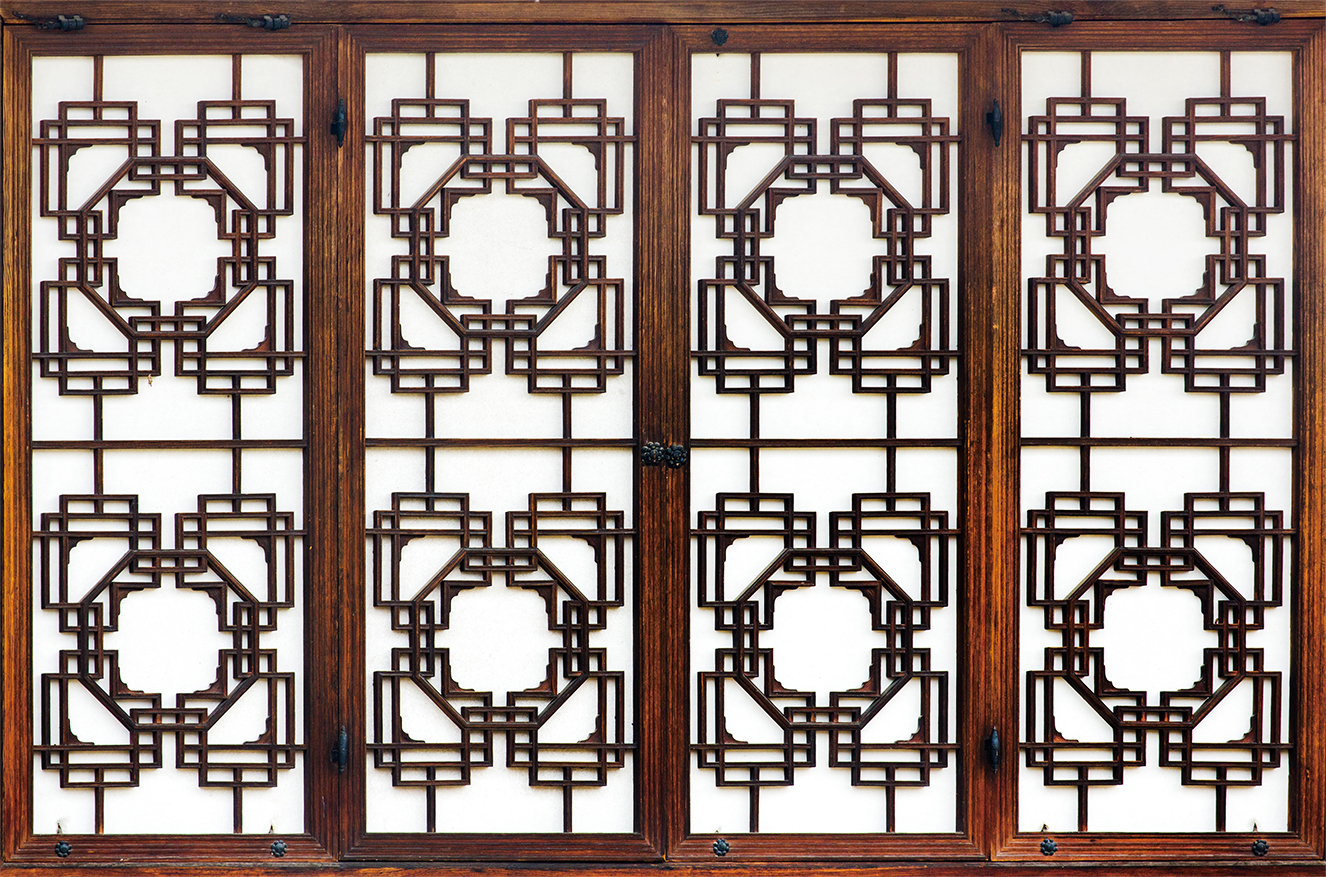

The door and windows of Korean traditional houses are coated in mulberry paper. But their remarkable lattices abound with symbolism―and are truly more than meets the eye.

If you have never seen a traditional Korean building up close in real life, finally getting to see one can be an aesthetic overload. There is often so much to take in that it is easy to miss key details. And if you are not sure what you are looking at, everything―including munsal, the wooden lattice frames that cover doors―can look like mere decorative flourishes. However, they are anything but. And in most cases their sometimes minimalistic, sometimes elaborate nature speaks volumes about what a building was once intended for.

Since antiquity, Koreans have been using the bark of the mulberry tree to create a sturdy form of paper named hanji. This material was not merely used by scribes and artists, however. It was also the primary building material for windows and doors. On a traditional house, munsal were used to hold the hanji in place, provide some reinforcement and also add aesthetic appeal.

But perhaps more important than any of these functions was the symbolic value of munsal. To help understand this, it pays to take a trip to Naesosa Temple in Buan, Jeollanam-do Province. This stunning temple was originally built in the 7th century, before being reconstructed in the early 1600s. The rebuilt structure is a marvel of carpentry, and its main hall was supposedly constructed without the use of a single metal nail.

Munsal are more than just frames for hanji. © clipartkorea

Here you will find the oldest-known surviving examples of munsal in Korea. At first glance, these appear to be simple floral-patterned decorations, but a closer look pays dividends. In fact, these are no ordinary flowers: They are lotuses. In Buddhist symbolism, the lotus flower is equated with enlightenment when in full bloom. The closed or partially opened bud, though, represents the steps a novice, monk or practitioner may take on their path to enlightenment.

As such, the bottom of one section of the munsal on the temple’s great hall shows lotus buds at the base, with a preponderance of full blooms at the top. Step into this room, meditate and overcome the travails of the material world, the munsal suggests, and you too may step toward the ultimate goal of Buddhism―enlightenment.

The munsal at the main hall of Jeongsusa Temple display brilliant designs influenced by Buddhism.

© CULTURAL HERITAGE ADMINISTRATION

Floral Fantasy

Temples all over Korea often provide the best place to go if you are in search of munsal variety. The greatest champions of Korean Buddhism, the devout Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392), encouraged the growth of a dynamic, vivid form of belief that valued the use of color, striking paintings, aromatic incense and engaging artwork. Although the original Goryeo munsal are lost to the ravages of time, their echoes can be felt in the temples that flourished in the hillsides to which Buddhist monks were banished after the more austere, Confucian rulers of the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910) took power.

Jeongsusa Temple, in Incheon, has colourful munsal showing multicolored blooms springing forth from a vase, bottle or pot at the base of the door. The flowers explode into red and blue blooms with verdant leaves all around. As well as the aforementioned enlightenment themes, there is yet more symbolism at play here: For Korean Buddhists, such a vessel signifies good fortune, virtue and purity.

Elsewhere in the country, you can sometimes find more pious patterns that resemble the contemplation objects used in certain forms of Buddhist meditation, as well as intricate carvings made to resemble monks, birds, water-dwelling creatures and even mythical beasts like dragons, sometimes intertwining with or relaxing on lotus leaves.

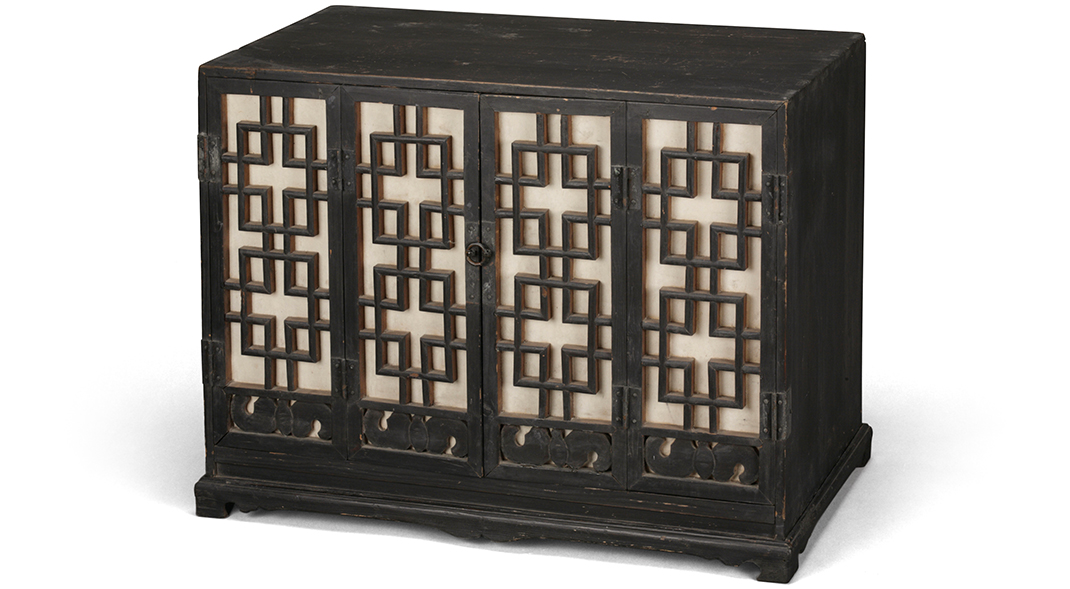

Joseon-era munsal embody simple, symmetrical patterns that reflect Confucian philosophy.

Secular Symbols

Such powerful messages were not the sole preserve of the religious world, or Korean Buddhism, however. In Korean palaces, you will often find that different buildings have very dissimilar munsal, something that is also true of the housing complexes the Joseon-era nobility used to inhabit.

For instance, the main reception chambers―where the Joseon king or family patriarch used to welcome guests―were often adorned with somewhat elaborate patterns. But the munsal lattices for the king’s consort, noble wives and the unmarried daughters of the king or patriarch were densely packed, which spoke of secrecy and closely guarded privacy.

The Confucian values of the Joseon rulers saw patterns like the lotus shunned. Instead, more minimal and simple―yet highly symmetrical―vertical bar patterns became en vogue, with a few horizontal patterns used at the foot, middle and top of designs.

This symmetry spoke of balance, modesty, harmony and understatement―the values that the Joseon Confucians put before all others.

Still today, new munsal creations can be found all over Korea as projects to build and restore traditional Korean folk villages gather steam. Some modern artists have even begun to incorporate elements of munsal in their sculptures and installation artworks―a fact that may one day help the ancient art of munsal gain recognition on a brand new, international scene.

Joseon-era munsal embody simple, symmetrical patterns that reflect Confucian philosophy.

Other Articles

-

Special Ⅰ A School for Families

-

Special Ⅱ Hub of Artistic Exchange

-

Trend Nostalgic Flavors

-

Hidden View Garden for All

-

Interview Composer Unsuk Chin

-

Art of Detail Magnificent Munsal

-

Film & TV D.P.

-

Collaboration Tradition Becomes Hip

-

Current Korea Korea’s Deeper Ties with UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt

-

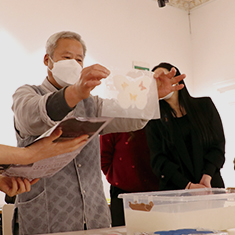

Global Korea Hanji Art Workshop in Italy