Magic Beasts

The Symbolism of the Creatures Featured

in Korean Royal Items

WRITTEN BY

Tim Alper

contributing writer

Photos courtesy of

National Palace Museum of Korea

The often-mythical animals that adorned the palaces of feudal Korea were not merely decorative: They had deep layers of hidden meaning that spoke of the many virtues of the nation’s monarchs.

Visiting a Korean palace is a feast for the senses―you will see people walking around dressed in traditional Korean clothing, centuries-old throne rooms, priceless antiques and so much more. In such a milieu, it can be hard to take in some of the more subtle nuances of royal palaces. The most important thing to note here, if you are on a search for a deeper understanding of what you see, is that symbolism is everywhere you look.

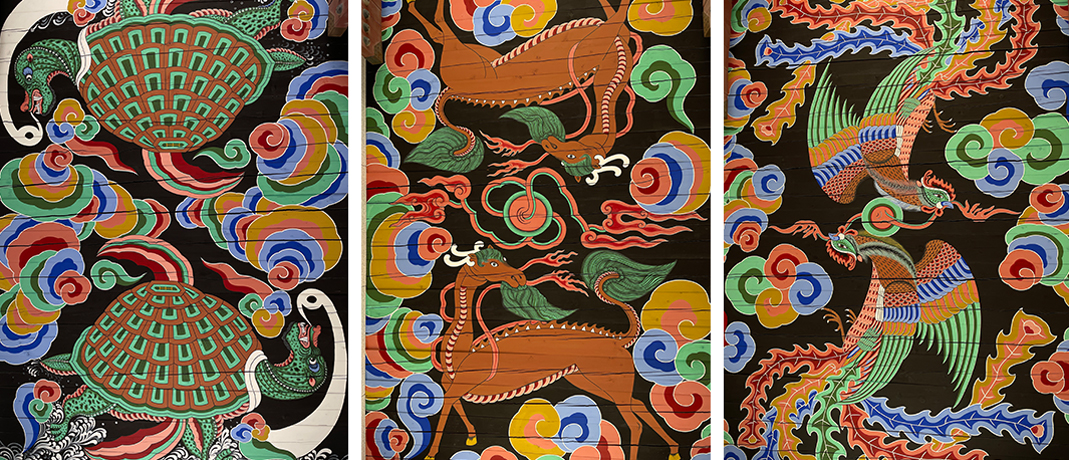

If you look carefully, you will notice that animal-related metaphors are embedded into just about everything: tiles, decorative details on walls, paintings and wallpaper. In years gone by, animals had great symbolic meaning to Koreans, and East Asians in general. In fact, they were used decoratively as signs, allowing even illiterate folk to understand what kind of person lived in a certain dwelling, particularly a palace. Many of these animals were mythical or extremely rare in Korea, and included the likes of white deer, red rabbits and elephants.

But a few legendary beasts were considered to be on such a high level in the celestial hierarchy that they would only appear in the presence of an unusually benevolent monarch: namely the gaseo.

The dragon motifs on the throne of the Joseon kings leave quite the impression.

Stunning Signs

The gaseo pantheon included the rarest of animals―some imaginary, others simply very highly treasured. They included the turtle, which explains why you will so often see stone turtles adorning the courtyards of both palaces and the most auspicious of temples. In Korea’s animist past, shamans used turtles as a soothsaying tool―claiming that they could predict the future by looking at the patterns on their shells.

Often these turtles were depicted on royal seals. Geomancers, too, thought the turtle to be a unique creature that inhabited a hinterland between the mortal and the divine. Its round or oval shell was thought to be a sign of heavenly perfection, while its square body was thought to represent the realm of mortals.

The turtle in an outdoor section of Changdeokgung Palace, in downtown Seoul, is a notable example. This turtle even features a flat rectangular patch on the top of its shell surrounded by circular shell sections, an echo of its marriage of the round and the square, the human and the godlike.

Mythical beasts on the roof of Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Gate. © STM

Fantastic Fauna

The turtle was unique among the gaseo for actually being a real animal. Far more steeped in fantasy and ancient religious allegory were the mythical beasts in this upper echelon of the animal pantheon. One of these was the gilin: a sort of unicorn-like animal with a fire-shaped mane, an ox’s tail, a deer’s body and a horse’s hooves.

This beast, ancient texts recounted, had a body designed for fierce assault. Yet in spite of its powerful arsenal of kicking and gouging weapons, it was considered to be a peace-loving animal. As such, just as the monarch represented the bridge between the Heavens and the Earth (like the turtle), the ruler also exuded an aura of gentle, merciful and virtuous power (like the gilin).

The gilin also had both male and female energy―an important notion at a time when the idea of carefully balanced harmony was treasured. Again, tiles in Changdeokgung Palace show this creature in all of its glory.

Another important animal here was the phoenix, which can be seen frequently in royal palaces. According to myth, the phoenix was a leader among birds: Where it went, other birds of all species were bound to follow. Again, one can see why the royal court was so keen to associate the creature with monarchs.

The robe of the royal family is adorned with phoenixes and a dragon.

The phoenix was thought to have one of a number of additional values depending on the color of its plumage and parts of its body. For instance, a white neck spoke of righteousness, while a black breast signified wisdom. Notable phoenix designs can be found at Gyeongbokgung Palace, one of the main palaces of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

The purity of the king’s heart, perhaps, was the virtue artists and royal court designers most sought to capture with another creature: a long-tailed white tiger with black spots. This animal was associated with extreme purity. It refused to eat anything that was alive, and would not even walk on living plants, such as grass and herbs. The beast would only appear in the presence of a particularly pure-hearted individual, legend explained.

Arguably chief among all of these animals, however, was the dragon, a creature associated with royalty in many parts of Asia. This is particularly noticeable in Korea’s royal palaces, however. The animal was believed to have the power to cause the wind to blow and the rain to fall―just like the kings of pre-Joseon times, who were thought to have benevolent powers over the weather.

To visit a Korean palace is to walk in the presence of these creatures. Unpacking their symbolic meaning can help you understand exactly what the court wanted Korean subjects of old to think about the people who governed them.

Other Articles

-

Special Ⅰ Playground for the Arts

-

Special Ⅱ An Industrial Zone Revived

-

Trend Old Warehouses, New Faces

-

Hidden View Colorful Ocean

-

Interview Soprano Seo Sun Young

-

Art of Detail Magic Beasts

-

Film & TV A Justification for ‘The Silent Sea’

-

Collaboration Harmony Between Familiarity and Novelty

-

Current Korea Korea’s New Year Goals: Recovery and Peace

-

Global Korea Opening Ceremony of the Korean Cultural Center