May 2021

May 2021

Chopsticks are much of Asia’s go-to eating utensil. And when it comes to crockery, while most Western households cannot get by without large, flat dishes, Asian cooks find bowls of various sizes equally indispensable. But travelers moving around Asia are often surprised to see that chopstick and bowl styles vary greatly from country to country.

Written by

Tim Alper,

contributing writer

Photo Courtesy of

Bangjjayugi craftsman

Lee Jong Duk

It was love at first sight for me when I first visited Korea and met the metal chopstick and rice bowl. Usually made of stainless steel, I found these utensils easy to use, exceptionally durable and incredibly easy to care for. I immediately bought a set of my own to take back to my native UK.

But although today’s low-cost, ubiquitous stainless steel rice bowls and chopsticks are quite modern innovations, visitors to Korea may be intrigued to learn that their origins are actually ancient and steeped in noble tradition.

To learn more about that tradition, it helps if you are lucky enough to stumble across a restaurant that serves royal-style Korean cuisine, and strives to create an ambiance fitting to the food. While ostensibly that might involve waiting staff wearing traditional Hanbok attire, wooden furniture and perhaps some gentle gugak (traditional Korean music) playing through the sound system, when it comes to eating, the biggest difference is often in the tableware.

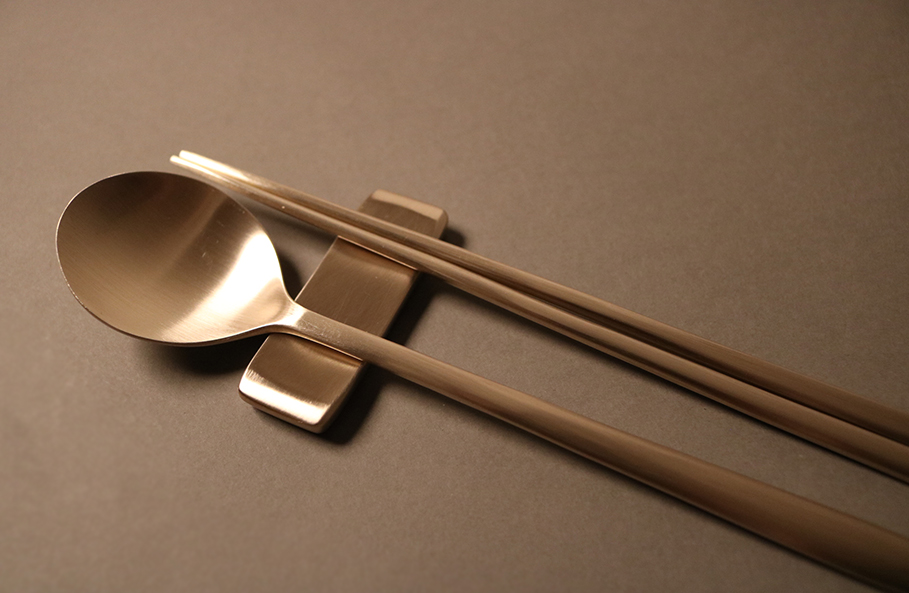

Although the concept of using the spoon and chopstick set you are presented with may be made of a much more eye-catching type of metal: bronze.

Back in Korea’s feudal past, only the rich and noble could afford to splash out on bronze tableware, or yugi. Common folk had to make do with wood or other materials. But although bronze chopsticks represented a costly investment even for the well-to-do, once you have eaten with yugi, you will instantly understand its appeal — and may even want to buy some for yourself!

Yugi has thus far, been commonly applied to eating utensils.

Yugi has thus far, been commonly applied to eating utensils.

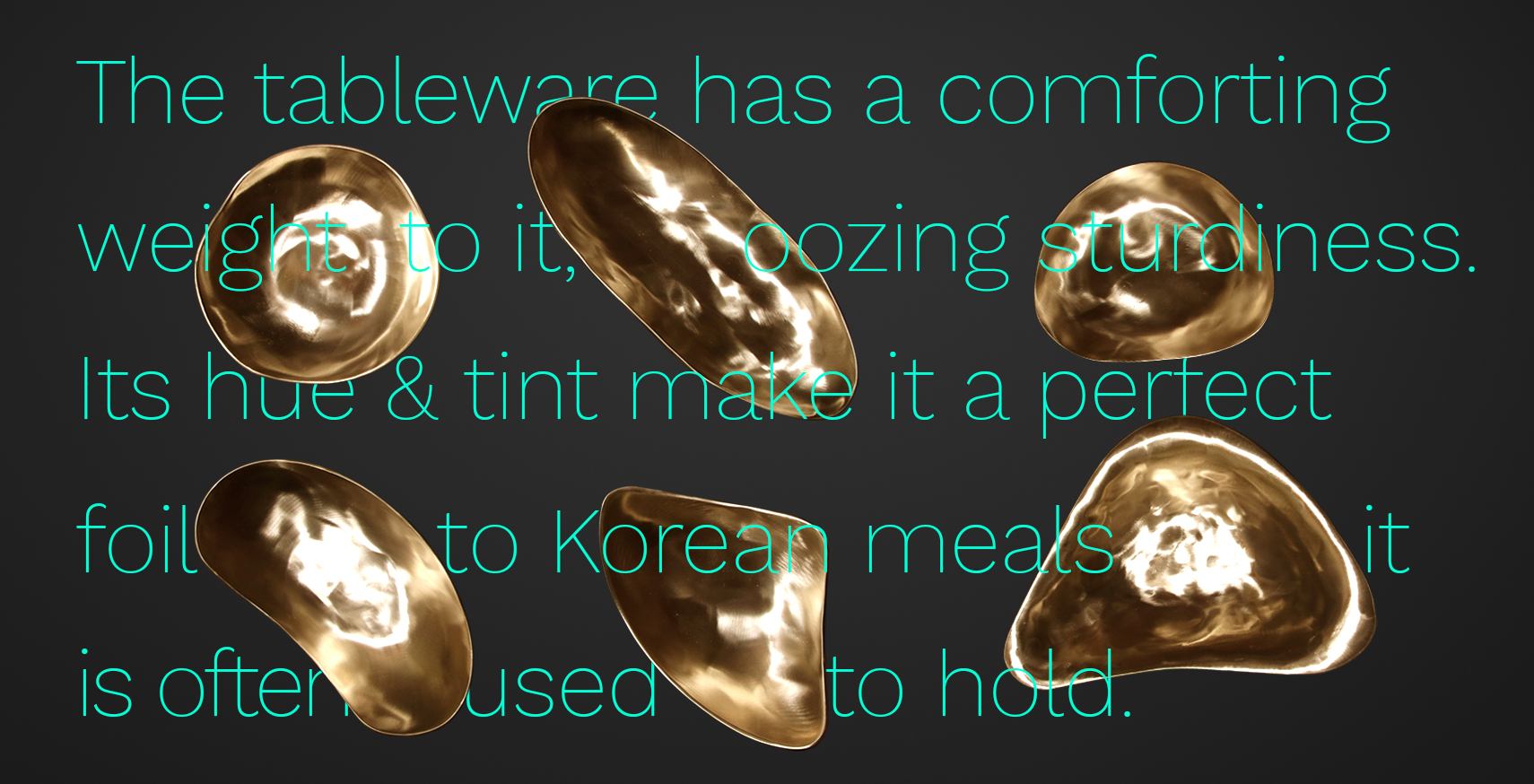

A pair of classic rice bowl and soup bowl made of yugi.

A pair of classic rice bowl and soup bowl made of yugi.

Yugi tableware has a comforting weight to it, and oozes sturdiness. It also has a stunning reddish gold hue that makes it a perfect foil to the steaming white rice that makes up the backbone of most traditional Korean meals. At once, you feel your mealtime has been elevated. It is almost impossible to bolt down your food hastily if you first need to remove a weighty bronze lid before you can access it.

It is also easy to understand why the ruling classes of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) were so enamored by yugi. The social elite was made up of seonbi (scholars), who prized high-minded values. For them, one can imagine, using yugi would have been a most fulfilling experience.

But it was not the seonbi, nor their royal masters and mistresses, who invented yugi. Archaeologists have found evidence that a large number of metalworkers made use of alloy-making technology to create bronze objects in the middle and late Silla Dynasty. The Silla monarchs ruled from the first century BCE to the 10th century CE, and their merchants used bronze in international trade deals.

Some of this early bronze-working prowess is still extant, such as the magnificent Bell of King Seongdeok the Great of Silla, forged in 771 and now on display at the National Museum of Gyeongju.

Yugi is applied to materials of wide-ranging sizes and forms.

Yugi is applied to materials of wide-ranging sizes and forms.

However, even in the Silla Dynasty, bronze was highly prized, and the idea of using for eating was outlandish to commoners, it was not so for the monarchy — for whom extravagance was the norm. Some rulers even actively sought out silver cutlery, believing that this metal reacted upon coming in contact with poison.

But customs involving silver utensils did not catch on outside the court — unlike yugi. While silver was rare in Korea, copper and tin were more plentiful.

Cooks soon discovered that using brass tableware not only gave their presentations an unprecedented elegance and an aesthetic boost, but also came with a whole host of other benefits.

Bronze tableware retains heat well, which is unusual for a metal. For Korean meals served with soup, broth or stew, yugi acts as welcome bonus. Metals like bronze can also be sterilized in boiling water, which makes them a smart choice from a hygiene perspective. And while not as stain-proof as modern steel, yugi is still more resilient to discoloration than many other materials.

Molding steely surfaces can attribute drastically different impressions.

Molding steely surfaces can attribute drastically different impressions.

Variants of yugi include jewelry trays and decorative items.

Variants of yugi include jewelry trays and decorative items.

Kingdoms came and went on the Korean peninsula while yugi’s popularity continuously grew. A perfectly preserved pair of yugi chopsticks can be seen on display at the National Museum of Korea, and dates back to the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392).

Historians believe that bronze chopsticks like these had become more common by the start of the Goryeo era. The simple design of this museum piece appears to indicate that these chopsticks were not intended for royal hands, but rather the dining tables of the petty nobility.

Rulers of the Joseon Dynasty expanded metal mining efforts across the peninsula, helping bring down the cost of bronze so much that eventually even the middle classes could afford them.

Making yugi is a painstaking process, a fact that goes a long way to explain why even today, a full set of bronze tableware does not come cheap.

The process of creating an alloy of copper and tin to an incredibly precise ratio, allows for zero room for error. Once a nugget is formed, it has to be hammered repeatedly until the utensil’s exact shape is finally achieved.

In today’s Korea, most households use steel chopsticks, as do restaurants, which also make extensive use of stainless steel rice bowls. Unlike yugi, these inexpensive utensils are very much dishwasher-safe, and represent a very economically sound option for most budgets.

But the Korean yugi tableware love affair is not dead. Indeed, a full yugi set of chopsticks, bowls and more is still a common and much-cherished gift for brides to present to their new in-laws.

And some contemporary artisans are working with yugi to produce eye-catching results that are fine-tuned to meet the needs of modern diners.

These include the likes of Lee Hyuk, a fourth-generation yugi artisan officially designated by the state as Proprietor of Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 72. Using distinctly 21st-century innovations such as 3D printers, Lee has brought back designs created by craftspeople who died long ago, leaving only their work behind them — and precious few clues about how to replicate them.

As such, Lee has managed to craft a range of bronze ware items that his forebears would never have dreamed of fashioning, including forks, trays and even jewelry. So eye-catching are his designs that he was selected to represent Korea at the renowned 2018 Maison&Object (MOM) fair in Paris — a sign, perhaps, that yugi is slowly carving out a niche for itself in the digital age.