May 2021

May 2021

King Yeongjo, the 21st king of the Joseon Dynasty, ate like a vegetarian despite being a top royal with access to all sorts of nutritious delicacies. Nutritional needs induced him to consume poultry (like pheasant or quail) and fish (like croaker) from time to time, making him more akin to a flexitarian. While other kings typically consumed five meals per day, Yeongjo ate three — each of which were of such small portion as to be a point of concern for cooks who prepared and served his meals. Put in our modern understanding of diet, his vegetarian tendencies and modest meals may have contributed to his longevity.

![]()

Written by

Ok Seil,

Magazine ‘P’ & ‘C’

editor-in-chief

The below excerpts are part of the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseonwangjosillok), recorded in the 13th year of King Yeongjo’s reign (1737).

“Catskin is great for curing ailments.” “I’ve witnessed some cats conversing, back in between and about the palace grounds, and simply cannot get comfortable with the thought of skinning them for a cure. Thus is precisely why I’m also averse to hunting cows and pigs.”

For context, Yeongjo was purportedly offered raw catskin to heal an ailment he had long been suffering from. Despite his physician’s multiple recommendations, Yeongjo stayed stern in refusal.

Yeongjo enjoyed a reign of 51 years, making him the longest to be throned during the five centuries-long Joseon Dynasty. The more widely known anecdotes or milestones in his life aside, intriguing tidbits like the above let us glean his philosophy, which diverged from the conventions of the time.

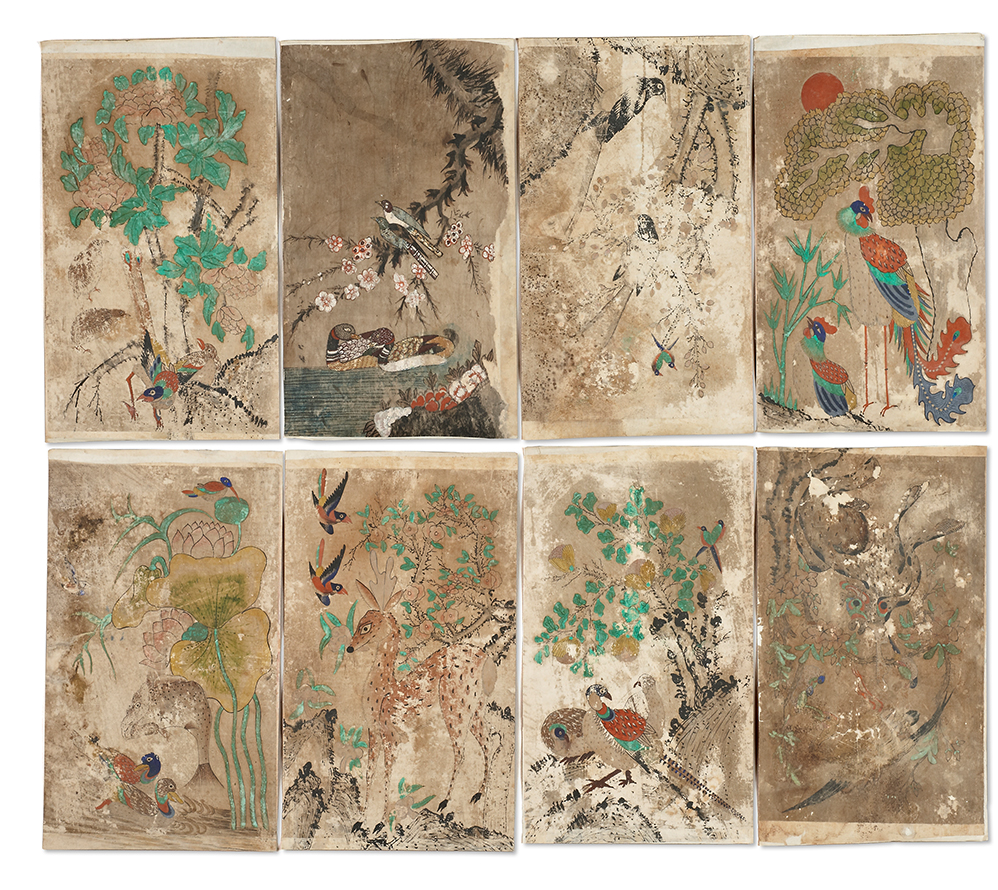

Ethnic-folk art (minhwa) like the series of eight hwajodo (drawing of birds and flora)

Ethnic-folk art (minhwa) like the series of eight hwajodo (drawing of birds and flora)

are replete with portrayals of Korea’s wondrous and once, exotic naturescape. © Seoul Museum of History

Pyon Sang Byok’s drawing of cats from the 17th century is comprised of ink on silk. Many of his works depict animals either domesticated, or in the wild. © National Museum of Korea

Pyon Sang Byok’s drawing of cats from the 17th century is comprised of ink on silk. Many of his works depict animals either domesticated, or in the wild. © National Museum of Korea

Yeongjo banned punitive measures of torture and violence, which had been in place as per ancient penal and judicial systems. Whereas other political leaders rarely hesitated to wield torture as a means of retribution, even going as far as to come up with more extreme and pain-inducing measures, it remains a source of wonder among historians why an authority-oriented leader like Yeongjo refused corporal punishment as a way of his wielding his power.

A clue that may help explain Yeongjo’s decisions lies in his own experience with traditional medicine in August of 1733. In order to alleviate an abscess that had been sore for quite a while, it was suggested that heat be used on the sore. Traditional medicine used mugwort or other herbal remedies to burn on an abscess. It was while undergoing this treatment that Yeongjo purportedly may have connected his own pain to those of prisoners. The incident is said to have led to his banning of cruel penal punishments that had been in place until his reign.

Yeongjo lived the longest of the kings of the Joseon Dynasty. © National Palace Museum of Korea

Yeongjo lived the longest of the kings of the Joseon Dynasty. © National Palace Museum of Korea

Going back to the cat episode, Yeongjo had been suffering from a chronic illness that gave him severe arm pangs. Since keeping the nation’s leader healthy was an absolute duty for palace workers, they explored all sorts of methods to cure their king. It is hence only natural for the royal physician to repeatedly suggest methods of optimal efficacy, despite Yeongjo’s repeated refusals. Stranger still was that Yeongjo had never seemed overtly animal-friendly; he merely asserted he was “simply unable to bear the thought of living creatures [the stray cats he had glimpsed here and there between the palace walls] being skinned” for his physical recovery.

Modern medicine owes much of its progress to the sacrifices of animals. Much of our remedial medication has been developed at the cost of living organisms. Many of those creatures have gone through human domestication, been dubbed “pets” and are part of our daily lives, considered “companions” with whom we live. While many like to point out there has been much progress in the way humans treat animals, humans are still no less egocentric in putting ourselves — humanity — first, above any other living being or priority.

In East Asian mythology, there’s a legendary creature called a tam. The mythological creature is a self-destructive being that not only consumes everything and anything in sight, but goes as far as to eat its own tail and then on — its own body and all — once nothing else is left to consume.

There simply is not enough innocent warmth, purity of perspective and naturally technicolored rays of light in our irises, the eyes with which we behold the nature that unfolds in and inhabits our planet. No longer are our eyes open to the outcries of animals in their last living moments as each minute brings them closer to extinction. We are too numb to sympathize with the fact that we swallow genetically manufactured beings that had never been granted the chance to become more than a mechanically engineered lump of protein designed for human consumption. Let us take a step back and reconsider our actions, whether or not putting mankind above all else has not degraded us into the likeness of tam.

Animal companions that are part of

modern life hopefully push humans

toward less human-centric acts.

© MESSE ESANG

© MESSE ESANG

The annual K-Pet Fair and K-Cat Fair, respectively, are co-hosted by MESSE ESANG and the Korean Pet Food Association.

This year, the former is held twice (in April and May, in Busan and Ilsan, respectively); the latter once in June in Seoul. Only the pet fairs permit pets’ entry. © MESSE ESANG

The annual K-Pet Fair and K-Cat Fair, respectively, are co-hosted by MESSE ESANG and the Korean Pet Food Association.

This year, the former is held twice (in April and May, in Busan and Ilsan, respectively); the latter once in June in Seoul. Only the pet fairs permit pets’ entry. © MESSE ESANG