Korean film remains a hot commodity. Hallyu, or the Korean Wave, is no longer a passing fad in neighboring countries. Korea is also becoming an alternative source of creative vision, even in the film industry, which has long been in the grip of Hollywood.

Writer. Soongbum Ahn

Korean Cinema After ‘Parasite’

The success of the film “Parasite” confirmed the potential of Korean video content on the global stage. If the movie “The Righteous Revenge” (1919) is considered the starting point of Korean cinema (which is somewhat debatable), then “Parasite” was the culmination of the field’s development over the following century. Sure enough, “Parasite” won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2019 and four Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, in 2020. It had the fourth-highest box office of a foreign film in North America and sold more than 10 million tickets at Korean theaters, the mark of a megahit.

After the striking success of “Parasite,” interest in Korean films began to surge in the English-speaking world, breaking through the “one-inch-tall barrier” of subtitled films. Purchase inquiries for Korean films rose dramatically in the European Film Market in Berlin in February 2020, and interest in the rights to remake films spiked as well. That led to curiosity about the full oeuvre of Korean directors, including films that had received little notice before.

A scene from the movie ‘Parasite’ ⓒ CJ ENM.

A scene from the movie ‘Parasite’ ⓒ CJ ENM.

How Korean Cinema Hit the Big Time

Korean cinema built the foundation for success on an industrial, cultural and institutional level in the mid- and late-1990s. Even in the early 1990s, members of the Korean film industry had been nervous at the prospect of opening up the market. Many leading filmmakers of the time took to the streets chanting slogans about safeguarding Korea’s “screen quota,” which requires cinemas to show local films a certain number of days every year. There was widespread pessimism that the Korean film industry could not compete with Hollywood films because of considerable technical and financial disadvantages.

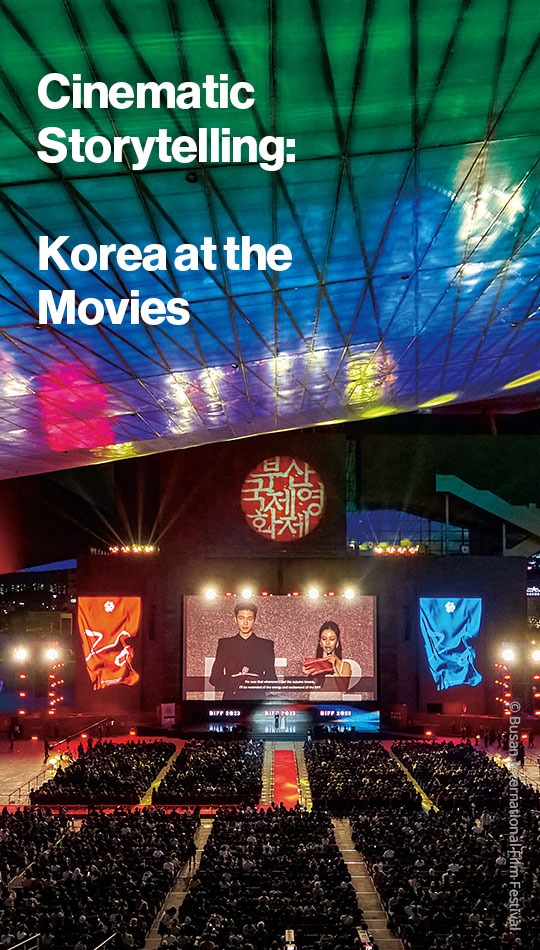

However, in the mid-1990s, the government became more committed to supporting and developing the Korean video and film industries. At the same time, a cinephile culture was forming that created more public arenas for discussing films. This was when Korean editions for “Screen” and “Roadshow,” as well as “Cine21,” “Kino” and “Premier” were published. In effect, a forum had been created for film discourse. The shift in online communication culture from bulletin board systems to the web brought a dramatic increase in channels for ordinary people to access, consume, appreciate and interpret films.

The inaugural issue of Cine21, a magazine primarily covering Korean cinema news ⓒ Cine21.

The inaugural issue of Cine21, a magazine primarily covering Korean cinema news ⓒ Cine21.

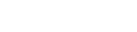

Notably, the Busan International Film Festival became a big success and the Jeonju International Film Festival established itself during this same timeframe. Film festivals served not only to uncover original directors and actors but also to attract new viewers to cinema. They provided branding opportunities for local governments and updated visitors on the latest cinematic trends both in Korea and overseas. Finally, they served as a platform for both supporting and distributing independent films and arthouse films on the periphery of commercial films.

The mid-to-late 1990s was also when dazzling auteurs such as Park Chan-wook, Hong Sang-soo, Kim Ki-duk, Lee Chang-dong, Hur Jin-ho, Kim Jee-woon and Bong Joon-ho jumped into the film industry. No single tendency, theme or style tied them together. The diverse charms of Korean films today are the result of these original directors being given the scope to exercise their talents.

Following the mid-to-late 1990s, Korean cinema revolutionized in nearly all areas: planning, production, distribution and consumption. The subsequent Korean wave in cinema was the natural consequence of a series of overlapping positive changes.

How Korean Cinema Wowed the World

The Hallyu has lasted for a quarter century now, but there are warnings of a crisis for the Korean film industry. Movie theaters, which once accounted for over 75% of the film industry’s total revenue, have lost their luster. During the pandemic, the film industry was embattled because of skittish investors, canceled productions and imploding film lineups, with films being shelved just before their scheduled release.

However, stepping back from conventional assumptions about film production, distribution and consumption, the risks facing Korean cinema today are outnumbered by the opportunities. For one thing, the advantages Korean cinema has gained over the years are now being disseminated through streaming platforms and various media channels. The overseas assessment of Korean cinema’s success thus far can be summarized in the following four factors.

First, the overall popularity of Korean video content is grounded in actors’ appearance and celebrity. Particularly in Asia-Pacific countries where the Korean wave has had the biggest impact, movie stars can still carry a film. The second factor inherent to the films themselves is that Korean filmmakers have a knack for using hooks when setting up the story. Even secrets about a character’s birth used to be an effective hook, although that has now become cliched through overuse in soap operas. Third, Korean films employ universally relatable plots that work for global audiences while still integrating quintessentially Korean elements into plot background, characters and episodes. “Parasite” dealt with social stratification and polarization, which are urgent issues for people around the world, but weaved them into specifically Korean spaces such as semi-basement apartments and cultural practices such as private tutoring. Fourth, Korean films seek out unpredictable cliffhangers and stereotype-defying characters while still providing generic pleasure to viewers accustomed to Hollywood films. Narrative grammar, audiovisual encoding methods and conventional characters are based on universal generic conventions. However, overseas pundits praise Korean films for their effective use of characters with unexpected choices and actions, as well as “tricksters” who can serve to raise or lower tension.

These are iconic film directors from Korea. From the top in order, Lee Chang-dong, Park Chan-wook, on the bottom right Bong Joon-ho and to his left, the actor Song Kang-ho.

These are iconic film directors from Korea. From the top in order, Lee Chang-dong, Park Chan-wook, on the bottom right Bong Joon-ho and to his left, the actor Song Kang-ho.

Korean Storytelling Takes Center Stage

To sum up, one of Korean filmmakers’ greatest strengths is their knack for knowing exactly when to employ various mechanisms to heighten narrative tension. Korean webtoons and web novels, which have come into the spotlight recently, neatly illustrate the distinctive characteristics of Korean storytelling. For instance, the much-discussed show Reborn Rich―which originated as a web novel and has also been published as a webtoon―involves a character who is reborn in the past in someone else’s body, a common scenario in Korean online content.

There are also encouraging signs of the Korean wave having a tangible impact on literature, where the language barrier is particularly high. One can perceive a gradual change in attitudes toward Korean literature in developed countries and English-speaking countries in particular, since Han Kang’s novel “The Vegetarian” won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016.

Visitors reportedly congregated to the Korean literature section during the 2024 Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, the biggest book festival in the United States. This is all reminiscent of when Korean cinema was beginning to reach a global audience in the mid- and late- 1990s. Another positive sign is that the total number of Korean literary works published overseas with support from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea continues to rise.

The next stage of the Korean wave ultimately depends on how the influence of Korean storytelling is used. That should also point to new opportunities for Korean cinema, which has already become its brand. I hope Korean storytelling’s influence across media and genres will create more room for mutually beneficial cultural hybrids.

Writer. Soongbeum Ahn

Director of K-culture·Story Contents Research Institute Kyung Hee University

Soongbeum Ahn is a professor in the Department of Korean Language and Literature at Kyung Hee University and director of the K-Culture·Story Contents Research Institute. He is an active film critic and poet, and previously served as a judge at the Busan International Film Festival and secretary-general of the Korean office of the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI). He was also the host of the Cinema Paradiso movie program on EBS.