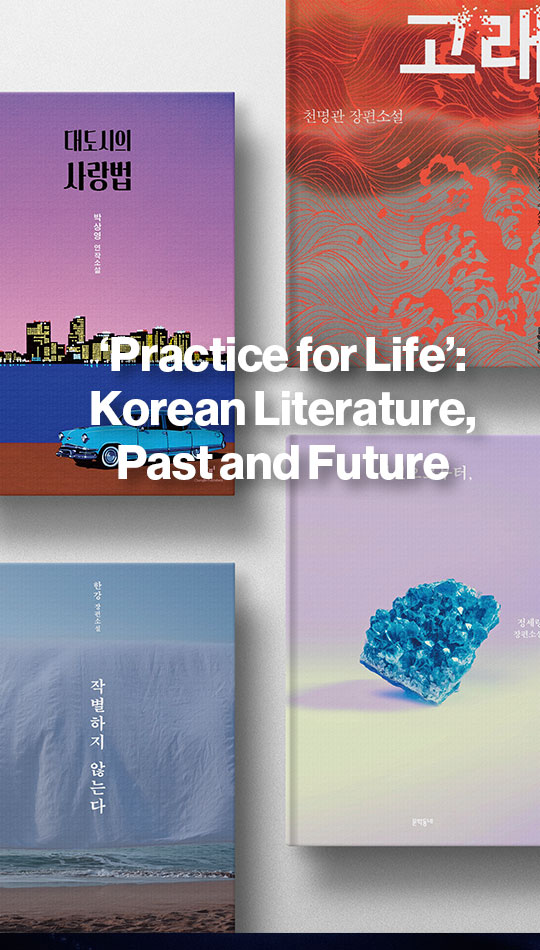

“Mom, I’m hungry for life,” Park Wan-suh said, borrowing the voice of the protagonist in “The Naked Tree” (1970). The novel’s motif was inspired by Park Soo-keun’s painting “The Naked Tree Awaiting Spring.” In the painting, two people stand before a desiccated tree without any leaves. On the left is a woman holding a child, and on the right is a woman with a basket on her head. The withering, lifeless tree symbolizes the series of historical tragedies endured by Koreans from the late nineteenth century to the present day. The two women symbolize the Korean people’s struggle to overcome such afflictions and rebuild their lives. This persevering spirit is often reflected in Korean literature. The indomitable will to survive and the thirst for self-preserving joy amid a continuing crisis are sentiments that have repeatedly blossomed on the pages of Korean literature.

Writer. Eunsu Jang

Desire, the Driving Force of Literature

The driving force behind Korea’s contemporary literature is the indomitable will to overcome continuing crises. Yi Injik’s “Tears of Blood” (1906), often considered the first modern Korean novel, begins with the line, “It seemed as if the roar of gunfire would blow away Pyongyang. But when the guns went silent, all traces of human activity disappeared, and all that remained on the hills and fields were the bloody bodies of the dead.” It’s a detailed depiction of how the warring imperialist powers of the early twentieth century fought for influence and power on Korean soil, turning the “Land of Morning Calm” into a blood-soaked land of death.

“Tears of Blood” illustrates a basic motif in Korean history: Korean livelihood and vitality have generally been stripped away by an external force. Korea lost its sovereignty in the early twentieth century to Japan. In the mid-twentieth century, the country was split into two along the ideological lines of the Cold War. In the late twentieth century, their lives and sense of community were swallowed up by the tides of globalization and neoliberalism. Today, Koreans confront an infernal abyss governed by the law of the jungle, every man is for himself. Yet amid such suffering and chaos, Koreans have never lost their creativity and their dynamic energy.

Koreans have achieved industrialization, rising to the ranks of developed nations. They built democracy from the ground up and are now a nation of robust democratic processes. They have also accumulated cultural capital and now spread their culture around the world through Hallyu, the Korean Wave.

Park Wan-suh’s ‘The Naked Tree’ is her first work set against the backdrop of the Korean War on June 25.

Park Wan-suh’s ‘The Naked Tree’ is her first work set against the backdrop of the Korean War on June 25.

A tree stripped of its leaves eventually withers and dies. Yet Park Wan-suh calls it a “naked tree” instead of a dying one. “The dying tree was visible from my dark, cramped studio apartment. Yet to me, it wasn’t a dying tree, but a naked one.” A dying tree and a naked tree may be similar in appearance but are different in meaning. A dying tree has resigned itself to death. A naked tree, however, is determined to survive in a world full of sickness and destruction. It represents the grit and determination to live out a decent life. As Park said, “I know a stubborn tenacity for the joy hidden within my being.” In an era when “the entire country was in darkness,” Park found light within the Korean soul, the indomitable will to someday take back their joy. That was the source of her literary output.

Novelist Kim Seung-ok referred to this indomitable spirit, resolute defiance in the face of death when your world has been ripped out from underneath you, as “practice for life.” While in prison for his dissent against an oppressive military dictatorship, poet Kim Chi-ha realized that life has the power to defeat death while gazing upon a plant that had managed to grow up through cracks in the cement. “It looked so vibrant on that particular day,” Kim recalled. “Tears formed in my eyes as the words, ‘Life, life’ seemed to ring in my ears.”

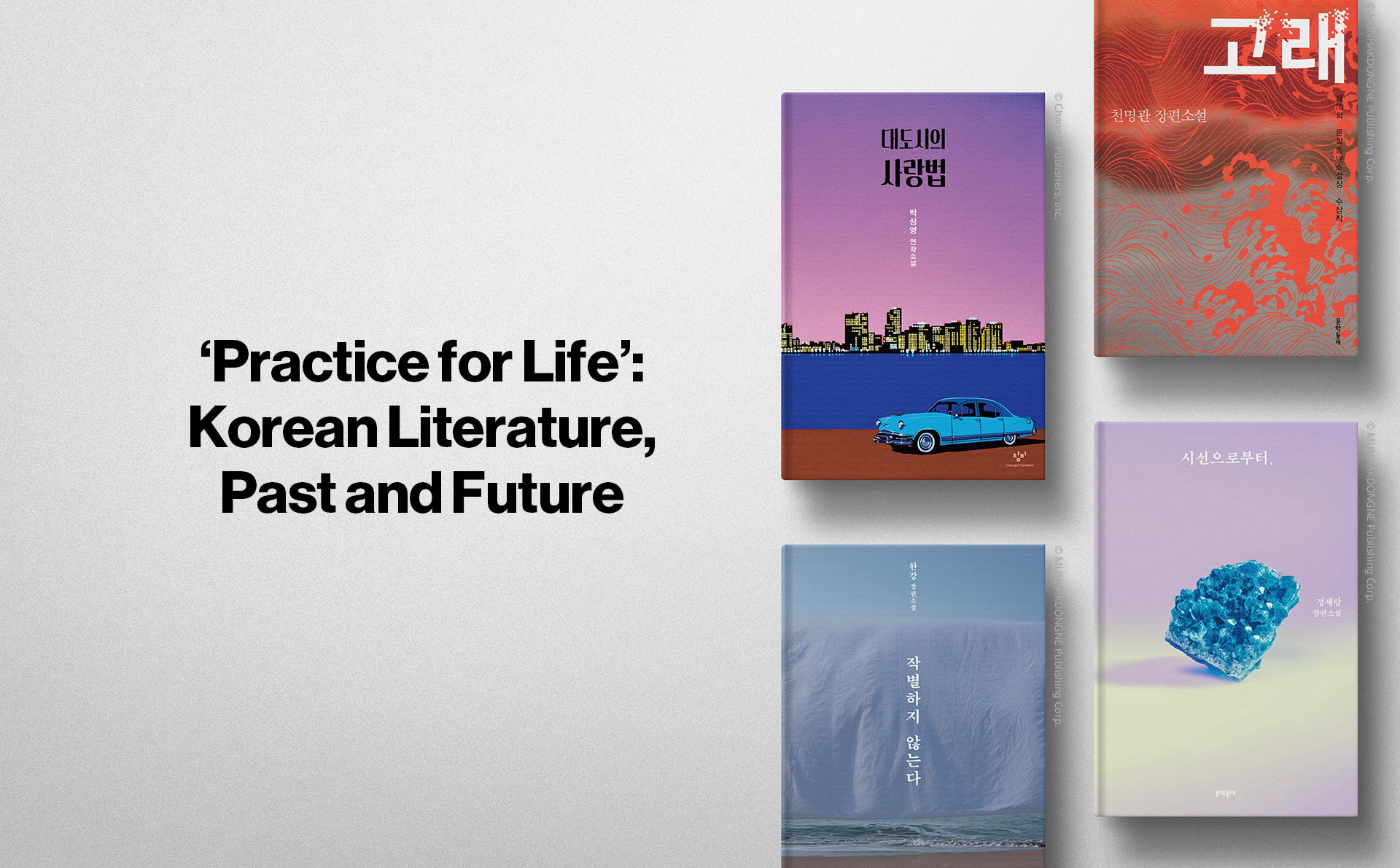

Yearning for the force of life, finding one’s niche in the face of disaster and crisis, the tenacity to recover your right to joy—these themes are also present in contemporary Korean literature. In her short story “The World’s Going to End Anyway,” Gong Hyun-jin, who debuted in 2023, writes, “I desperately clung to the desire to live. I want to live. I want to live even more.” Korean literature’s achievements over the past century can be found in the flowers of language blooming on these naked trees that are hungry for life, defiant against the harsh realities of imperialism, the Cold War and neoliberalism.

Korean Literature Today

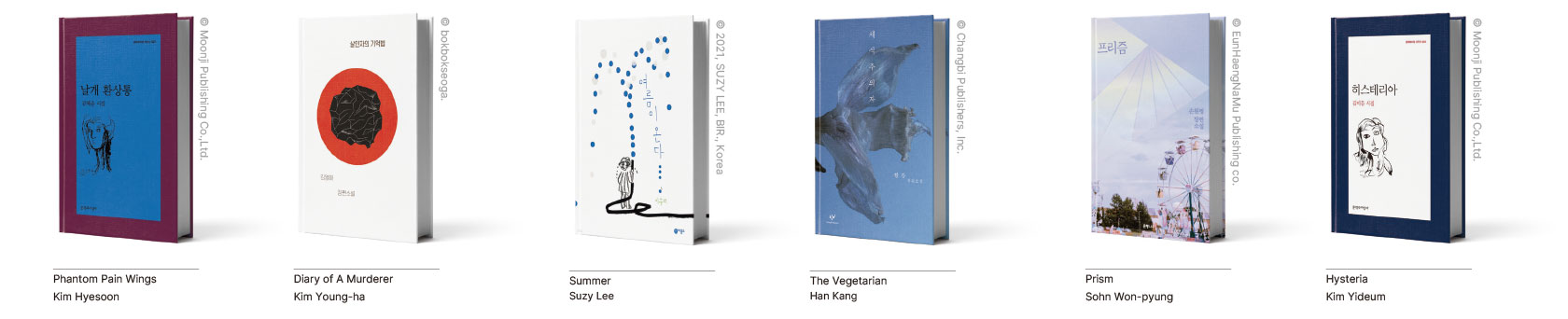

After Han Kang’s novel “The Vegetarian” won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016, the various flowers of Korean literature have been blooming in fields across the world. Over 200 titles of Korean literature are translated and exported to overseas markets every year. More titles are being published in more countries with each passing year, and an increasing number of Korean literary works have either won or been nominated for overseas literary prizes. The poetry of Kim Hyesoon (National Book Critics Award, U.S.) and Kim Yideum (National Translation Award, U.S.); the novels of Pyun Hye-young (Shirley Jackson Award, U.S.), Yun Ko-eun (CWA Dagger Award for Crime Fiction, U.K.), Kim Young-ha (Japanese Translation Award), and Sohn Won-pyung (Japan Booksellers’ Award); the graphic novels of Kim Keum-suk (Eisner Award, Harvey Award, U.S.); and the picture books of Suzy Lee (Hans Christian Andersen Award) are all among the prizewinners. Young writers like Bora Chung, Kim Cho-yup and Park Sang-young are gaining momentum as well.

Perhaps the most defining characteristic of modern Korean literature is its intersectionality. Korea managed to modernize at an unprecedented pace. Since being forced to open its borders to the outside world in 1876, it has undergone constant crises at the crossroads of tradition and modernity, the Asian continent and the Pacific Ocean, East and West, imperialism and democracy, liberalism and communism, regression and development, and all while developing at the speed of light. In the 1950s, Korea was an agrarian backwater with an average income of around 150 dollars a year. Today, it’s one of the world’s twenty largest economies, a country boasting cutting-edge technology. As a BTS member mentioned at the United Nations, Korea was invaded and decimated before being divided—but now it’s in the global spotlight.

An extreme obsession with the future, the inability to be satisfied with the present moment, being locked in a relentless struggle, the desperation to achieve modernity, a fierce competition for material wealth—these are the pride as Koreans, as well as their wounds. Having squeezed two centuries of Western modernization and industrialization into just a quarter of the time, Korean literature is a faithful witness to those injuries and struggles. But just as Park Wan-suh reinterpreted a dying tree as a “naked tree,” ready to meet a new spring, Korean literature has fostered a new language of the Korean people amid the backdrop of imperial invasions. This language has allowed us to reflect on the meaning of nature and ecology amid the modern race toward development. It has preserved the desire for national reunification amid the pain of division. It has protected the spiritual integrity in the commercial deluges of materialism. It has nurtured dreams of individuality and women’s liberation in a familial and patriarchal society. Modern Korean literature has protected the ideal of a life of human dignity in a society that places the responsibility for the yawning wealth gap on individuals, a world that emphasizes competition and self-exploitation. Imagining a new type of community based on that dignity is the sober duty with which literature has been charged down through the years.

Female writers in Korea have had stunning achievements since the 1990s, tracing the “dark side” of Korea’s rapid economic development in sharp and sophisticated language. One example is found in the first lines of Kim Hyesoon’s poem “Phantom Pain Wings”: “Bird in high heels / walks on asphalt, crying / Mascara drips down.” The high heels, asphalt and mascara symbolize Koreans’ modern life; the crying represents a life of sadness and grief; and the running mascara hints at a distorted visage. Together, they form a triptych of the pain suffered by Korean women in the rat race for success or survival. While that could be said for women in all societies under the thumb of the patriarchy, it also stands for the pain inflicted on all people forced to conform to modernization and globalization.

These women writers’ prose has striking characteristics as well. Rather than Western-style novels, they are masters of Korea’s typical “small narratives.” These do not neatly map onto short stories in the Western mode, which tend to rely on irony. Korea’s small narratives siphon political, economic and social issues into a passing moment of individuals’ life, while delicately pondering the meaning of life contained therein. Such stories also examine how social issues can be overcome through communities based on bonds that are traditional, but neglected by patriarchal societies—such as the bonds between mother and daughter, and between older and younger sisters.

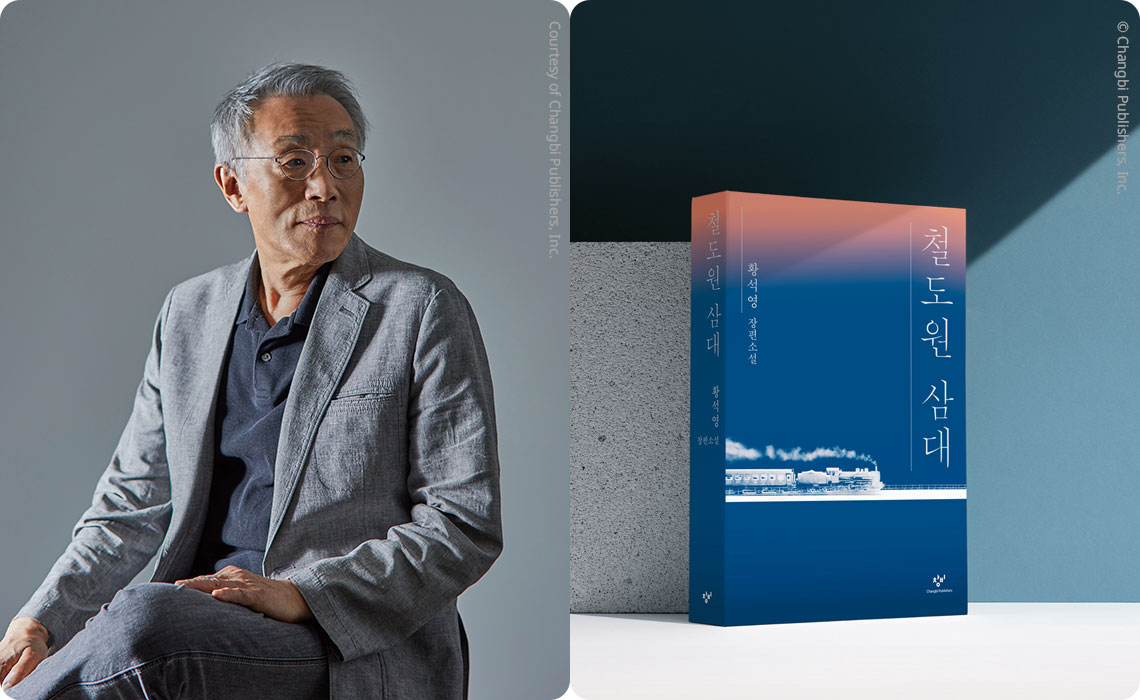

(Left) Hwang Sok-yong, the author of ‘Mater 2-10,’ which has been shortlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize.

(Left) Hwang Sok-yong, the author of ‘Mater 2-10,’ which has been shortlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize. (Right) The cover of the Korean edition of ‘Mater 2-10’

Korean Literature Embraces the World

The novellas that have received so much attention in Korean literature as of late try out various experimental forms to expand upon Koreans’ hunger for vitality, struggle for joy and practice of life as they strive to find their ecological status in the midst of that reality. That is contextualized amid the struggle for survival ensuing from the disastrous effects of climate change and the continuing impact of neoliberalism and globalization following Korea’s dazzling economic growth. The apocalyptic narratives that frequently appear in these novellas are a metaphor for the pervasive despair in the world around Korean and their efforts to somehow create a haven for life. If Korean literature today appeals to readers around the world, that’s because it guides them on an intense journey of self-discovery through which anyone can find hope and consolation.

Eunsu Jang

CEO of the Edit Culture Laboratory

Eunsu Jang is CEO of the Edit Culture Laboratory. He helped produce books at Minumsa while serving as its CEO. He develops tools for thinking about reading and writing, and about publishing and media. His works include “The Future of Publishing” and “Reading Together, Living Together.” He has translated such books as “The Giver” by Lois Lowry and “Gorilla” by Anthony Browne.