September 2021

September 2021

The media and entertainment industries hardly used the term “fandom” before the 2000s. Instead, the expression “fan” or “fan club” was common. The status of fans greatly changed when the suffix “dom,” meaning “realm” or “a condition,” was attached to it.

Written by

Lim Jinmo,

pop columnist

Illustrated by

JB

Photo courtesy of

Yonhap News

Back in the 1980s when the Korean singer Cho Yong-pil started a modern pop sensation, which later evolved into K-pop, the term ‘Oppa Budae’ (Troopers) fascinated the public. It was a newly coined term referring to a horde of passionate female fans screaming “Oppa!” for a male celebrity. The singer, now in his early 70s admitted that fans’ support did play a huge part in his success. During his 2003 interview, Mr. Cho spoke of his fans with whom he shared memories and big moments in his life. “I make up a large part of their memories in their youth, so even as the ‘Oppa Budae’ has become ‘Ajumma [Older & Married] Budae’, they haven’t forgotten about me and continue to support me. To me, they are a source of strength.” But fans in those days tended to be more reserved in their support for the singer and did not actively display their influence as a collective group.

Behaviors of such fans started to change during the 1990s. The most famous prodigy boy band at the time, Seo Taiji and Boys, spurred the social power of fans. In addition to supporting the group, fans started to be more proactive and vocal on their own. In 2003, Seo Taiji’s fan club became so angry at an entertainment TV show they believed did not treat Seo Taiji and Boys fairly that they forced advertisers to cancel sponsorship. The incident became the first such case in the Korean entertainment industry, which was solely dictated by the fans.

This instance attested to the fan club viewers’ power to create a movement to express disapproval about a poorly made TV program. This event could be seen as the onset of the so-called “fandom” culture that’s more self-driven and aggressive. But even if fandoms could influence the social status of a singer, the group as a whole did not wield much power to control the star’s popularity. For example, fans could not directly affect the chart ranking determined by broadcasting stations and media that counted record sales and postcards.

Toward the late 1990s when the age of idols officially kicked off, fandom became a real force determining the idol’s popularity. The fans of H.O.T. and Sechskies, the two hottest boy bands at the time, openly declared, “We will make our Oppa’s newest release No. 1!” Subsequently, the two songs “Light” by H.O.T. and “Couple” by Sechskies won the joint grand prize at the 1998 Seoul Music Awards. The music industry professionals interpreted the result as a collective effort by fervent fans of Sechskies who did not want their idol to lose his spot against the rival H.O.T.

Their effort went beyond supporting the singer’s pride to supporting his popularity. This would mean the contest from then on would be held not only between idols but also their fan clubs. Many argue that the age of idols embraced the evolved core through which fan clubs staged their own contests alongside idols who competed with their artistry and talents.

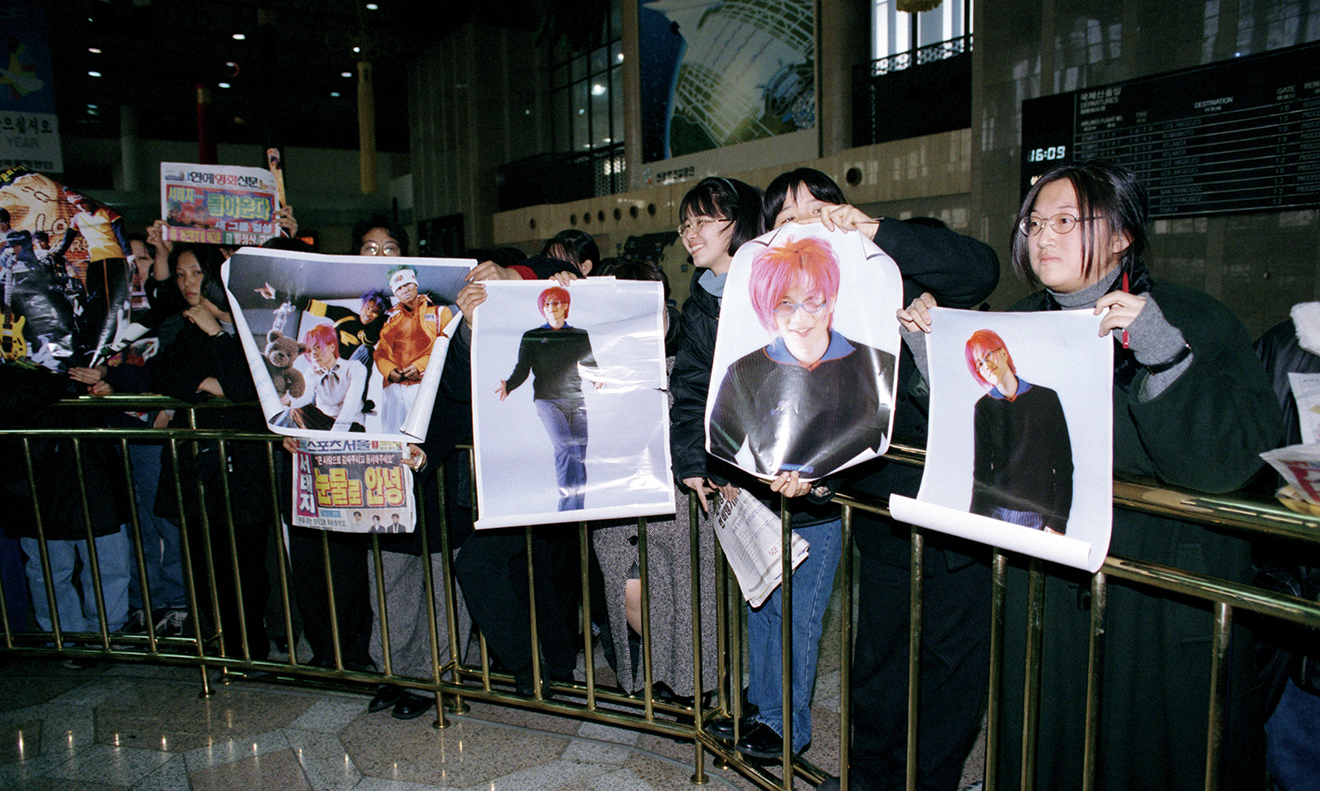

Fans of Seo Taiji and Boys gather at the airport.

Fans of Seo Taiji and Boys gather at the airport.

Going with the trend, idols and producers had no choice but to accept this change in trends and mindset. To gain wide popularity, companies supplying sound sources used to roll out marketing and promotional campaigns for random individuals. From here on, they were able to achieve enough success merely by managing a large number of fans wielding influential power.

Fans that belonged to a specific group did more than simply liking the pic posts of their idols. They formed their own communities and expanded their influence while creating a brand image. In other words, fans and their star developed something like a psychological symbiotic relationship.

Their relationship dynamics have become horizontal and collaborative rather than vertical as between a superior and subordinate in the 1970s and ’80s.

In the 2010s, the format of fandom went through another transformation. The brilliant performance of K-pop artists on the global stage led to the expansion of fan groups to the global arena. Blackpink, CT, and Seventeen are already well-known, but the boy band BTS can never be omitted from mention since the global fame of BTS’s fan club “A.R.M.Y.” found all over the world is truly noteworthy.

Behind the phenomenal success of BTS’s songs and contents in the global market is the absolute power of its fans, who march like a powerful army alongside BTS.

Analysts attribute the success of the song “Dynamite” and “Butter” that simultaneously debuted and shot to No. 1 on the single charts to the actions of BTS’s “A.R.M.Y.” and multinational fans. As the experts predicted, since the mighty power of “A.R.M.Y.” will not fade away, BTS will continually make strides on the path of global success.

Fans and stars developed a psychological

symbiotic relationship.

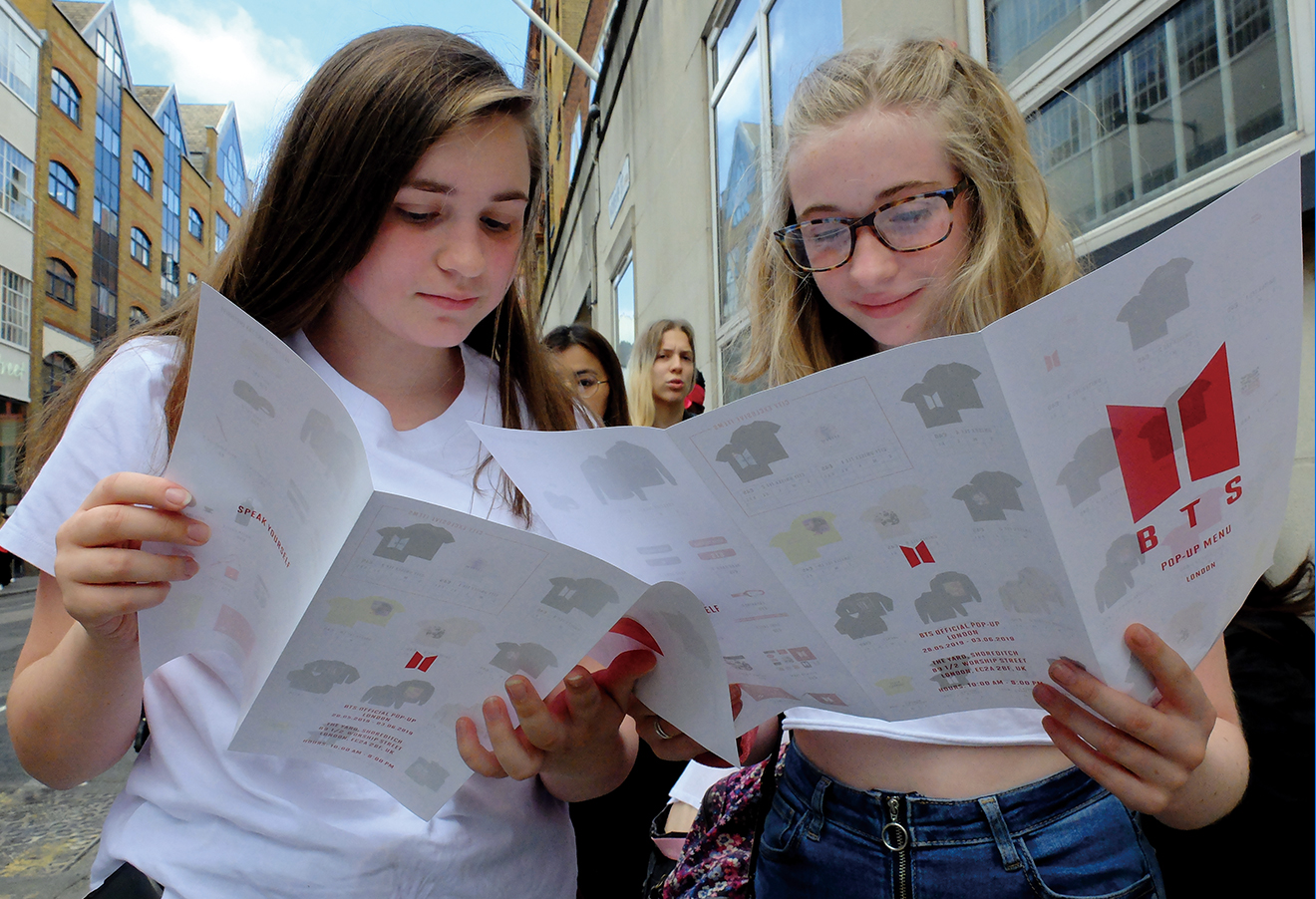

International fans of BTS browse a brochure at a BTS pop-up store.

International fans of BTS browse a brochure at a BTS pop-up store.

Concerning fandom, there is another noteworthy trend: namely, the advent of a rice donation culture with an aim to promote domestic rice consumption. In the name of their star, fans donated sacks of rice decorated with flowers and ribbons for various social causes. It is a kind of noblesse oblige extended by fans. During the 2010s, the fans of VIXX, B1A4, Shinhwa and Mamamoo took part in the rice donation movement.

Over time, the existence of fans has transformed from being merely an audience and supporters of the protagonist. This transformation refers to the vastly different nature of the music industry today. As shown by the ranking on the Billboard Hot 100, the reality is linked to the power of fandoms that determine idols’ ranking on the chart, exceeding their musical artistry. More and more, the Korean music industry is ruled by fandoms.