Culture Vulture

The Sun Always Rises

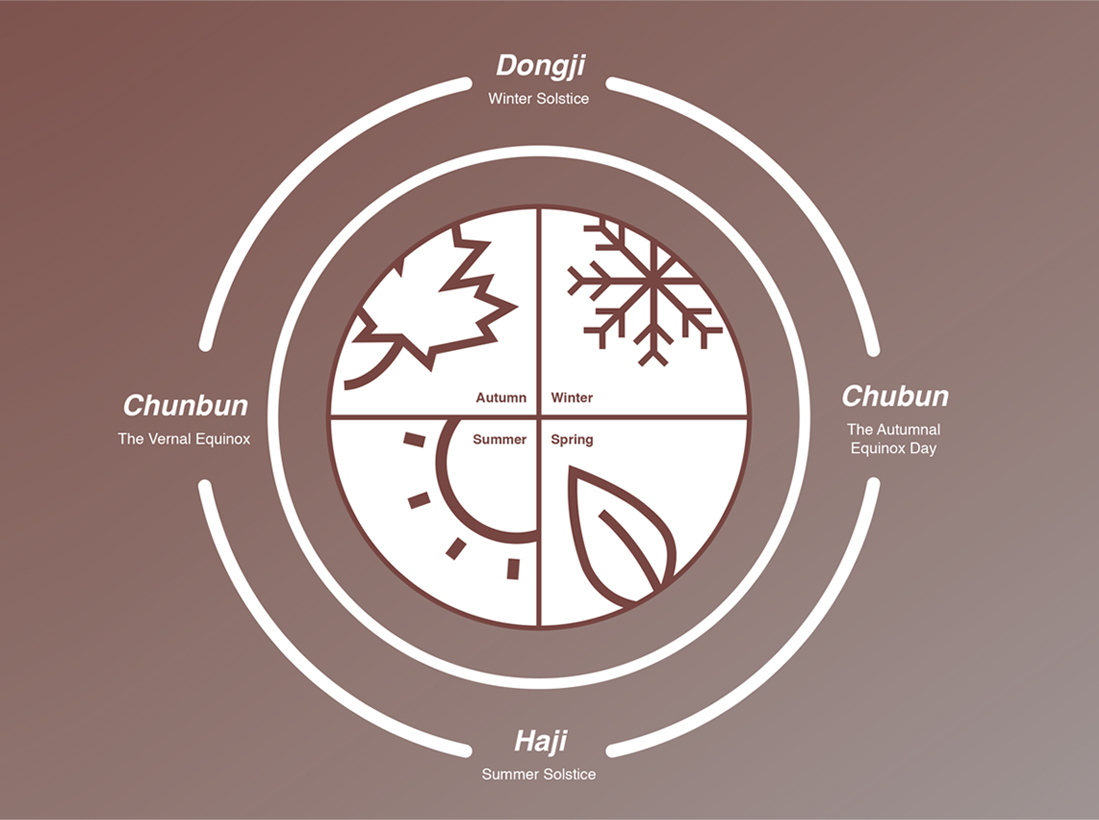

Korea’s 24 Solar Terms

Written by • Tim Alper

Though Korean TV is always entertaining, my favorite program of the day isn’t the latest hit drama or a star-studded variety show; it’s the daily weather bulletin. Why? In addition to the always-important weather news, weathercasters also provide timely reminders of upcoming calendar events that many non-Koreans — and even younger Koreans — are unfamiliar with.

Koreans mark two weather events in December. Daeseul refers to a midwinter peak, the day with the highest expected snowfall of the year according to tradition.

Dongji is the winter solstice and the shortest day of the year. Koreans traditionally mark this day by eating the mouthwatering dish patjuk, or gruel made of slow-cooked red or adzuki beans with deliciously sticky rice balls.

Served piping hot, this stomach-soothing preparation is a real boon on a cold winter day. And as Korea in late December often sees the mercury drop below zero Celsius, a large bowl of patjuk is just what the doctor ordered.

It’s also what the shaman ordered. Patjuk’s distinctive deep red color is thought to bring good fortune in the year ahead, as an old superstition believes this color helps ward off evil spirits. Korean villagers used to make this dish as offerings to deities at shrines, and even threw hot ladles of patjuk around the main entrance of their homes to ensure that malicious sprites stayed at bay.

Some Koreans even believe that a particularly cold Dongji foreshadows a bountiful harvest and a good year ahead.

Lunar vs. Gregorian Traditions

Ipchun usually occurs in winter, often during snowfall. © clipartkorea

Such rich traditions are still observed in Korea on a smaller scale year-round.

To the untrained eye, there seems to be no pattern to their occurrence. For instance, I often wake up on a frosty early morning in February and turn the radio on, only to be told by a Korean announcer, “It’s Ipchun today,” or the start of spring. With the streets covered in snow and weeks of subzero temperatures ahead, spring seems a very long way off, Ipchun or not.

Or conversely, you might wake up under a baking hot sun in early August, with weeks of sweltering hot weather ahead before the cooling winds of late September arrive to fan the blaze. And a TV news anchor might say this is Ipchu, which literally means “the day fall enters.” The irony of talking about autumn on what is often one of the hottest days of the year is never lost on me, and presumably many Koreans

On days like this, you can vividly feel that something is out of sync, and not without reason. There are 24 solar terms per year including Dongji and Ipchu that correspond very neatly to the calendar, just not the one most of us live our lives by.

Modern Koreans make use of the same Gregorian calendar as most other nations, but this wasn’t always so. For most of Korean history, the lunar calendar was the only one people paid any heed to. The same goes for other East Asian nations including China, Vietnam, Japan and the Ryukuan culture of what is now Okinawa, Japan. All of these cultures had their own versions of the 24 jeolgi (solar terms). Matching these events up with Gregorian calendar dates can be a tricky matter.

Cherry blossoms decorate many alleys and streets during summer. © clipartkorea

Time to Sow, Time to Reap

Many Koreans still lean heavily on the lunar calendar. The nation’s two biggest holidays are linked directly to it: Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving) and Seollal (Lunar New Year). Some only choose to celebrate their birthdays according to the lunar calendar.

But the solar term calendar is much more than an amusing curio; it speaks volumes about the way Koreans lived their lives for centuries, how they observed the world around them and how they marked each passing mini-season.

While the Hebrew scribes of the fourth or fifth century B.C. were writing “to everything there is a season,” East Asian wisdom seekers some 8,000 km to the east were spelling out almost identical sentiments at almost exactly the same time.

Summertime in Korea is especially lush. © imagetoday

The Classic of Documents, an ancient Chinese text sometimes attributed to Confucius, contains the first known reference to Dongji. It also details the painstaking efforts that ancient scientists from this part of the world took to measure time, make farm-ing-related decisions and more in the leadup to the late second century B.C., when the 24-term solar calendar was eventually finalized.

The entire list makes fascinating reading, as it comprises solar events such as all four solstices and equinoxes and temperature observations like Daeseo, or the “great heat” of late July. But it also includes observations about wildlife such as Gyeongchip, the day when hibernating frogs awake from their seasonal slumber, and farming-related phenomena such as Mangjong, the seed-planting peak.

Kings and queens might have sat on the throne in pre-modern Korea, but the intricacies of agriculture, wind, rain, sun and ice were the real rulers.

As such, a huge range of customs, religious beliefs and superstitions has built up over the years to accompany the passage of the 24 solar terms. Few of these were documented by ivory tower scholars, who preferred what they considered more noble pursuits. Common folk kept only oral records of their solar term-linked traditions, meaning that the vast bulk of these are lost forever.

Chuseok is followed by Sanggang, the 18th of the year’s 24 solar terms that usually sees the first frost of winter and marks the end of the harvest season. © clipartkorea

What historians do know about the way people marked these events, however, is eye-opening. Korea is one of the few countries with two festivals dedicated to the harvest, so its agricultural tradition runs deep. In addition to the aforementioned Chuseok, which originated from a different folk custom, one of the 24 solar terms is also dedicated to reaping the bounty of the fields.

Sanggang, usually coming in late October per the Gregorian calendar, marked the end of the harvest season. This was the last chance for farmers to save their remaining crops from the devastating ravages of frost. After toiling all day in the fields to harvest the crops they spent the hot summer cultivating, Koreans would drink a liquor brewed from chrysanthemum as the sun’s rays faded over the horizon.

And when the agricultural season got off to a start in Gogu (late April), they would get ready to do it all again, praying fervently for rain. A dry Gogu was a bad omen, farmers believed, as it was thought to signal a drought-filled summer.

So the next time you catch a Korean weather bulletin, keep your ears pricked for unfamiliar vocabulary. You might just learn about a traditional celebration you didn’t know about or a fascinating way to commemorate it.

Much of Korea comprises mountainous topography. © clipartkorea