Culture Vulture

Centuries of Harmony

3 Inspirational Korean Instruments

Traditional Korean music is as accomplished and dynamic as the country’s history. While the nation’s indigenous instruments shares qualities with those in other countries, most notably in East Asia, each still boasts a singularity in sound and characteristics that attest to the uniqueness of Korean culture.

Written by • Tim Alper

Traditional Korean music is full of rich variety and makes use of a host of instruments not found elsewhere in the world. The following three are among the most notable.

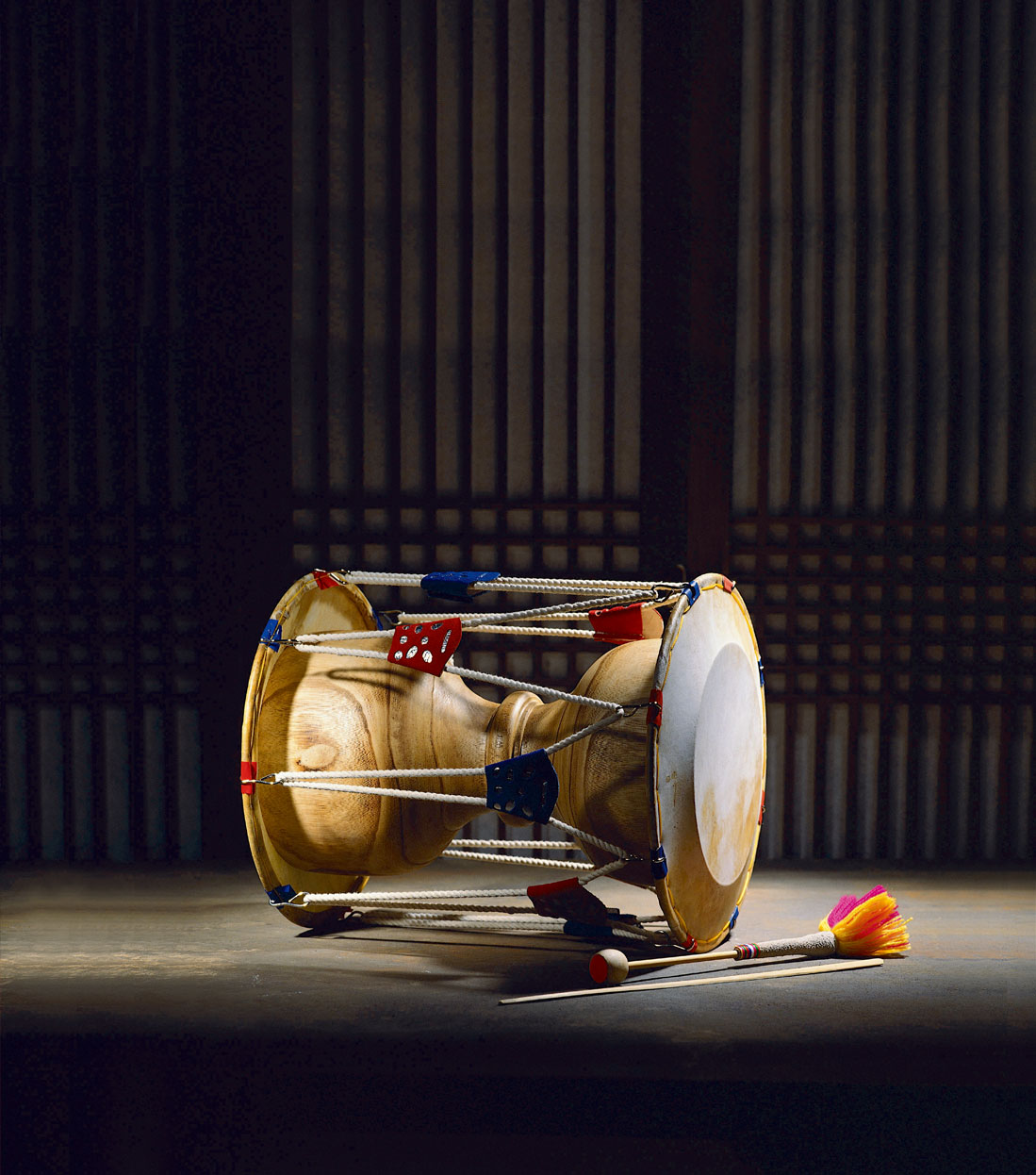

Beat of Different Drum

© imagetoday

Drums arguably take center stage in most forms of Korean music. The scores of Korean drum types vary from small and portable models to massive pieces that require mounting on poles, requiring drummers to strike their skins with both hands.

Percussion in Korean music, however, plays a considerably different role thanit does in other cultures such those in as Sub-Saharan Africa or Europe. In the West and Africa, drums provide the rhythm that drives a piece of music, or a beat. Traditional Korean music has no beat per se, though many modern artists of fusion music do create oft-bewitching beats using Korean drums.

Instead, Korean drums typically provide a form of punctuation or color to a piece of music, weaving in and out of the song at key moments rather than providing an ever-present beat. The best example of this is pansori, a one-person lyrical opera that has the singer basically performing acapella and a lone drummer providing often unexpected and impromptu musical responses to the story.

Possibly the most iconic of all Korean drums is the janggu, the most distinctive Korean instrument of its kind thanks to its shape. Hourglass in form, this drum is designed for dynamic performances and versatility, with two heads that look identical but produce very different pitches.

Once you witness a drummer perform with one of these instruments, you will instantly understand the secrets of the instrument’s lasting popularity. While most drums are designed to be played seated, this is every inch a dancer’s instrument worn on a diagonal shoulder strap. And though most drummers elsewhere are traditionally male, the janggu is a truly unisex instrument

Many male drummers play the janggu seated, as shown in the 18th-century painter Kim Hong-do’s timeless work “Mudong (Dancing Boy).” But some female players incorporate the drum in breathless dance-drum performances, made more mesmerizing when performed in an ensemble.

Usually crafted from Paulownia trees native to Korea, this drum is designed to be light and played either with hands or bamboo sticks. They produce a range of sounds from gentle taps or clapping sounds to the kind of earthy boom expected from a Western bass drum.

The gayageum boasts a wide range of pitches and thus boasts a greater presence and bigger body than other Asian zithers.© imagetoday

Superb Strings

The zither is the most iconic of all Asian instruments. Ask a Korean to name a Korean traditional instrument and the first name from their lips is the gayageum. Nothing quite expresses the soul of East Asian music like the plucking of gayageum strings.

To the uninitiated, East Asian zithers can look similar as they are often finger-plucked by seated (usually female) musicians and crafted from varieties of Paulownia wood. Zoom in for a closer look, however, to notice a world of difference as the gayageum requires no pick to play it.

The gayageum also traditionally has 12 strings, one fewer than the Japanese koto. The Chinese guzheng traditionally has 16 strings and the Vietnamese dan tranh 14. Modern zither variations in all four nations have blurred this key difference, with some models equipped with up to two dozen strings.

The main difference is not seen but heard, however. The timber of the gayageum is in a class by itself, and the instrument can hit high notes but really comes into its own in lower bass notes, giving it more presence and body than other Asian zithers.

Little is known about the gayageum exact origins. The 12th-century historical work “Samguk Sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms)” claims the instrument was invented in the sixth century A.D. by a ruler of the southern kingdom of Gaya (an area that encompasses much of today’s Gyeongsangnam-do Province). But this is likely apocryphal and hard to verify.

Regardless, the instrument was an integral part of the Korean musical scene by the 10th century, when the Goryeo Dynasty took power. This period was something of an early golden age of Korean music, giving birth to gayageum models like the now-defunct 15-string daejaeng.

The instrument’s second heyday came in the mid-to late Joseon Dynasty, peaking in the 1800s when sanjo music became popular. This dynamic form of music features meshing a large selection of disparate and usually fast-paced melodies together, often with dramatic effect. The genre’s popularity was so great that it led to the design of a narrower and streamlined gayageum with smaller finger spaces ideal for lightning-paced finger work.

Sanjo is arguably the best way to get immersed in gayageum music for a beginner in Korean music. Virtuoso musicianship is needed to perform the genre, which perfectly showcases the instrument’s distinctive sounds.

Folklore says the daegeum was crafted on behalf of a dragon’s expla-nation during the seventh century. © imagetoday

Wind Power

If the janggu and the gayageum are the heart of Korean music, wind instruments constitute the soul. Nowadays, the flute-like daegeum has grown almost ubiquitous, mainly because its often wistful tones are so well-matched with the silver screen. Often the most melancholic or surging parts of Korean film soundtracks feature this instrument as a backing or solo instrument, particularly period dramas or movies.

Made from bamboo, the daegeum has as its first syllable dae, meaning "large," distinguishing it from its smaller sister instruments, the junggeum (medium) and the smaller sogeum (small). The daegeum, however, differs in that its size and girth make it harder to play for longer periods of time and is also the only one of the three with a buzzing membrane. All of these factors contribute to a deeper and bass-rich tone.

The daegeum’s origins are shrouded in mystery. Folkloric stories tell of how a sea-dwelling dragon explained to a seventh-century monarch how best to craft the instrument from a large stick of dried bamboo.

Yet archaeological records tell a different tale. One of the earliest daegeum-like instruments found — by 18th-century builders — is now housed in a museum in Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do Province. It has never been dated but is made from jade rather than bamboo, and has twice as many air holes. Some say the item dates back to the Silla Dynasty (57 B.C. – A.D. 935), but this claim has never been substantiated.

What is certain, however, is that by the 12th century, the daegeum was found all over the Korean Peninsula. Its popularity has never waned over the centuries despite a long and winding musical journey that has seen it used by court performers, sanjo players and most recently artists of fusion music.

Like the janggu and the gayageum, the daegeum is the sound of Korea’s past and present, and as Korean music continues to evolve, very probably its future.

Unlike its sister instruments junggeum and sogeum, the daegeum has a buzzing membrane for producing a deeper bass-rich tone. © imagetoday