When popular online game “StarCraft: Remastered” players select the Korean server, they are greeted with the warning message: “The Land of the Calm Dawn has mastered the art of war, and emerged as home to the most renowned StarCraft players on Earth. Do not arrive idle to this melee.” No grandiose message of this sort is displayed on the servers of any other country, indicating Korea’s status in the world of online gaming. But while Korea is renowned around the world as a country of talented gamers, that’s a relatively recent development. Korea’s gaming culture has developed rapidly within 30 years reflecting diverse aspects of its modern society.

Writer. KyungHyuk Lee

Cultural Taboo on Entertainment After the Korean War

Koreans weren’t always very serious about gaming―just the opposite, in fact. When digital games first appeared in the late 1970s, Koreans had a considerable antipathy to games and other aspects of entertainment culture.

The devastation of the Korean War had left Korea without much economic infrastructure to speak of, leading Koreans to regard hard work as the greatest virtue. In that atmosphere, recreational activities were viewed as something of a vice. The pervading ideology in Korean society was the one embodied in Aesop’s fable “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” which applied not only to adults but also to school-age children. The idea that children should always be studying dominated Korean culture at the time.

So when video arcade games began to trickle into Korea in the 1980s, they were treated like the plague. The new video arcades were branded in most media as dens of vice. All video arcades added the label “intellectual development” to their marquees, a plaintive reminder that games and play were not to be enjoyed for their own sake but as a type of study that could benefit the intellect.

The screen shot of StarCraft: Remastered © Blizzard Entertainment

The screen shot of StarCraft: Remastered © Blizzard Entertainment

Gaming Craze Spreads Through Computer Education

Korea’s rapid economic growth began to get tangible results in the 1980s, fueling the formation of a broad middle class. Members of the middle class had more disposable income to invest in their children, one manifestation of which was the home computer.

In 1989, the Korean government announced it would require computer education for elementary school students to train them for future industries. That made a big impact on education-conscious Korean parents. Academies teaching computer skills sprouted up around the country, and many families bought home computers to ensure their children had the education they needed for the future.

But back then (just as today), kids had little interest in using those computers to study. Instead, the home computer fad served to massively boost the game-playing population. Those home computers effectively became children’s gaming devices, and computer skills academies hosted informal swap meets where games circulated freely. Thus, the computer education boom of the late 1980s is one of the main reasons that computer games have a much larger share of the market than console games in Korea, in contrast with Western countries.

As computer bulletin board systems began to proliferate in Korea in the 1990s, enthusiasts of various kinds congregated in clubs on the online bulletin boards. Just as most of the first generation of songwriters who helped shape today’s K-pop originated in hip-hop, pop and rock clubs on those early bulletin boards, it was in various online clubs that the first generation of Korean game developers came together to swap ideas about making domestic games. The digital boom that had begun with computer education would prove fertile soil for the heyday of Korean gaming in the 2000s.

A Gaming Powerhouse Created Through Crisis

The year 1998 was when the roaring Korean economy ran off the road during the Asian Financial Crisis. As a series of bankruptcies and layoffs at big conglomerates caused crippling unemployment, the government sought to reorient the economy towards the IT industry. The widespread installation of high-speed internet cables gave birth to the unique service known in Korea as a “PC bang,” or LAN gaming center. Those centers facilitated multiplayer online games like StarCraft, which was released around that time.

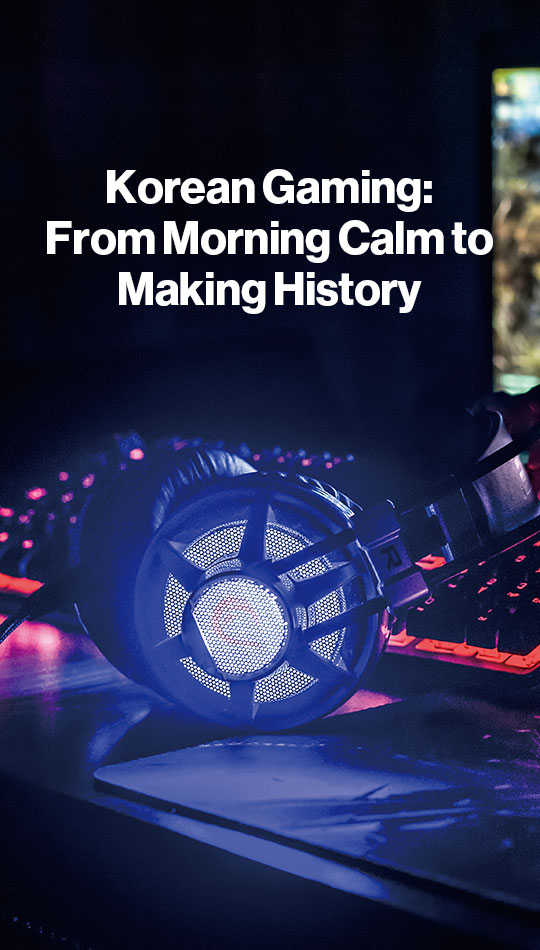

StarCraft was a sensation that swept through LAN gaming centers around the country, proving that this new entertainment medium was fully marketable in Korea. It was ironic that the StarCraft craze occurred amid the lingering trauma of the Asian Financial Crisis, but that also foreshadowed changes in the Korean media industry after the 2000s. Backed by the robust infrastructure of the country’s “PC bang,” numerous locally produced online games such as “Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds” and “Lineage” achieved enormous success, which began to nudge Korean culture in the direction of online games in the 2000s.

Gaming Culture, an Integral Part of Korean History

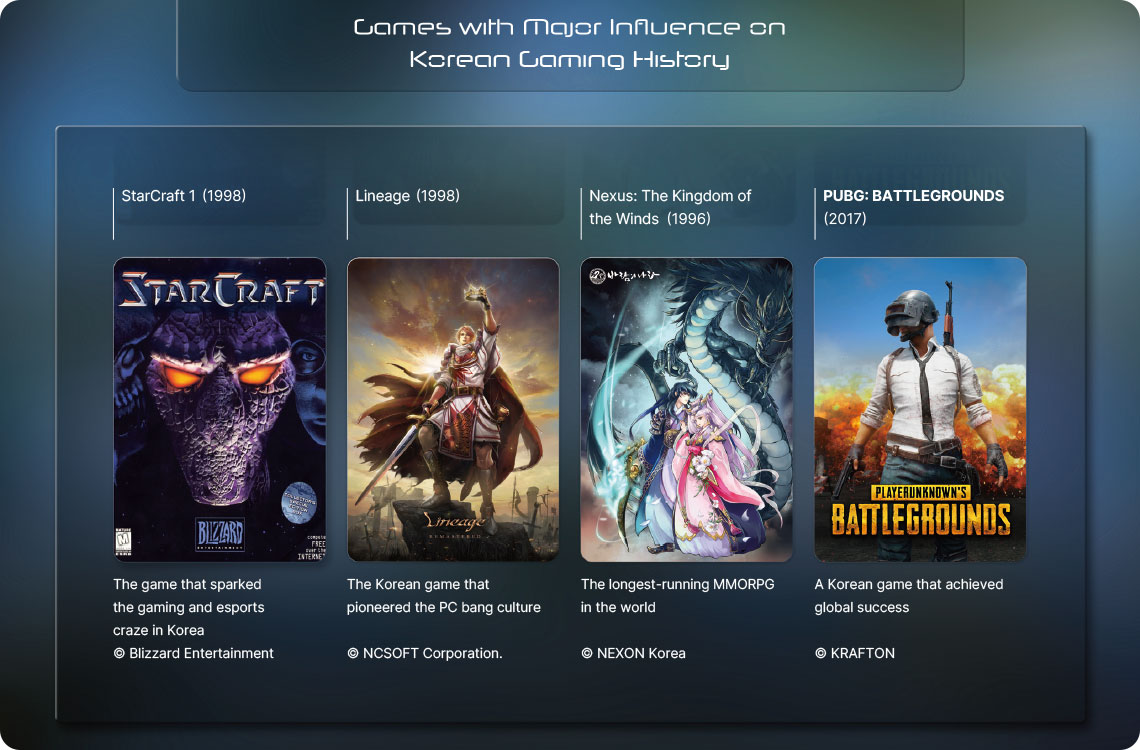

When asked which country has the world’s best gamers, many are likely to consider Korea the obvious answer. The presence of numerous video game heavyweights―such as Lee “Faker” Sang-hyeok, “the unkillable demon king” of League of Legends; Lim “BoxeR” Yo-hwan, who helped give birth to the genre of esports; and Bae “Knee” Jae-min, the world’s best player in TEKKEN―ensure that Korea is the country to be deemed a gaming “powerhouse.”

The Land of the Morning Calm’s transformation into a land of passionate gaming is a relatively recent development. The change reflects more than a mere fondness for fun; rather, it is the product of various twists and turns in Korean society. The stigmatization of entertainment following the chaos of Korea’s independence and the Korean War led to an educational drive for digital literacy following economic growth, and the resulting computer gaming boom turned Korea into an online gaming powerhouse after the Asian Financial Crisis. Perhaps it is time to recognize Korea’s relationship with gaming as being an integral part of its contemporary history.

KyungHyuk Lee

Editor-in-chief webzine Game Generation

Lee is a game critic and cultural researcher who studies how digital games interact with society. He is the editor-in-chief of the game criticism webzine “Game Generation.” He has published books in Korean titled “The Birth of the Payment Play” and “Game Theories,” as well as a paper titled “Is buying game items part of play? : a study on the expanded concept of ‘game play’ with the change of payment methods.”