August 2021

August 2021

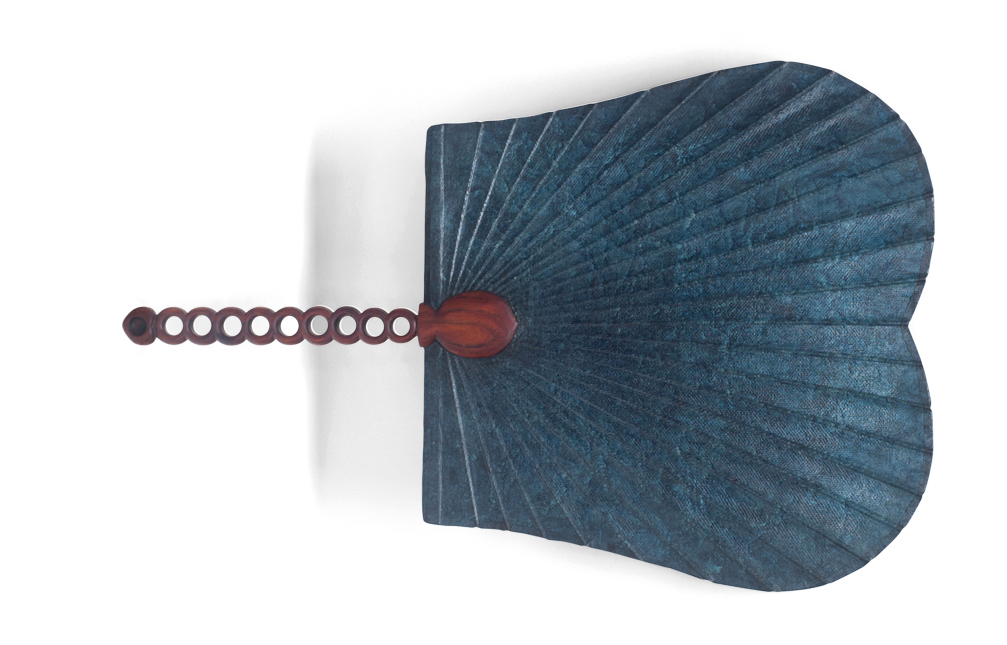

The peacock-shaped gongjakseon is the most splendid of Korea’s traditional fans. Reserved for royal use only, the unfolding fan not only kept kings cool, but looked great doing it.

Written by

Tim Alper,

contributing writer

Photo Courtesy of

Jeonju Fan

Culture Center

If you have ever visited Korea in the summer, you will know just how hot and sticky the months from June to August can get. Koreans have been wise to airflow-based cooling methods for centuries. Even in the modern era, when air conditioning units are ubiquitous and electric fans are everywhere.

It pays to pay attention to the unique shape of these free hand fans―essentially a wide, almost circular fan with a stick-like handle. For non-Koreans, they do not look exactly as one might imagine a hand fan to look. But for Koreans, their shape is comfortingly familiar.

Traditional fans come in two distinct forms in Korea. The first, and most familiar for Westerners, is the folding or collapsible fan. Ubiquitous across much of East Asia, this kind is also still common in Korea, and is an essential prop for the main performers of pansori, a traditional form of rhythmic song and storytelling. These fans can be snapped open and shut with dramatic effect.

The second is the danseon fan, a somewhat less diverse, but arguably more striking fan. Like the folding fan, it is usually made of bamboo, which makes it light in terms of weight. But unlike its folding cousin, it is rigid. With a firm central holding stick, it has a number of broad spokes or ribs, which are traditionally covered in paper or silk.

During the late Joseon period, traditional handicraft underwent a golden age, and the danseon began to diversify. By the 19th century, noble women were often seen with danseon featuring oiled paper and brass fastenings that held the bamboo handle and the paper covering in place. Many of the designs were almost totally circular, with some much squarer, or with heartshaped tops and straight edges at the bottom. The most ornate had lacquer finishing that made use of the sap of deciduous trees native to Korea.

Craftspeople and patrons alike were keen to add unique flourishes and patterns to these fans, decorating them with calligraphic flourishes, lines of poetry or hand-painted details. But the most common design―one that endures today―involved the use of the sam taeguk. It features a swirl of colors intended to represent harmony. But unlike the bi-color red-blue design on the flag, the sam taeguk fan adds an extra hue: yellow.

The variety did not end here, though. While the sam taeguk fan is a favorite tourist souvenir and a popular craft item project for young schoolchildren, a lesser-know, but certainly more striking design was reserved exclusively for royal use: the gongjakseon.

This fan was designed to look like a male peacock spreading its tail feathers. But unlike peacock-feather fans, popular in various other nations, this fan actually made no use whatsoever of feathers. Instead it was a danseon fan carefully crafted to resemble the bird.

There was a royal twist, however. Korean rulers were not expected to fan themselves: Instead this piece was wielded by a servant, who used the fan to keep the air flowing around their monarch and shield them from the sun.

As such, the piece was somewhat larger (and heavier) than a typical danseon fan. Its handle was made of high-quality chestnut, ginkgo or pine wood, although the spokes radiating from the center were usually made of bamboo. Artisans would carefully treat the wooden handle over a fire so they could give the piece attractive curves they could then use to chisel into the shape of a peacock’s head and neck, replete with a beak and crest. This piece was then coated in lacquer.

A high-grade paper was then mounted onto the spokes, which were also carefully curved to resemble the arching form of real peacock plumage. The paper was decorated accordingly, using the peacock’s distinctive feathers as a color guide.

And the hard work did not end there. The paper was then covered in finely ground soybean powder and coated with sesame oil in a process that was repeated several times before a final rubbing process, adding an attractive gleam. Pieces like these were extremely hard to come by in the past, and the historical and archaeological record provides scant clues on their origins. One intriguing clue is to be found in the pages of the Samguk Sagi, a historical document about the history of the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BCE to 668 CE). The document was published in the 12th century, and also contains information about the early Goryeo period in the early 10th century.

One passage in the record describes how a Later Baekjae (892-936) monarch gifted a gongjakseon piece to the ruler of the Goryeo―indicating that both royals were indeed the sole owners of these rare items and that 12th-century readers would have been familiar with them.

Fascinatingly, gongjakseon craft is still alive and well in modern Korea: Lee Gwanggu, an artisan in Seocheon, a county in Chungcheongnam-do Province, is recognized by the government as a master artisan of the intangible craft of fan-making.

Seocheon has remained the spiritual home of gongjakseon making for decades ―Lee inherited his knowledge and title from his father before him, meaning that the gongjakseon tradition will continue into the immediate future. Should Lee pass on his skills to a disciple, there is every chance new generations of Koreans will continue to learn about the gongjakseon―and perhaps buy a piece for themselves.