July 2021

July 2021

As a symbol of the state or the powerful families which inhabit them, royal palaces the world over are known for their beauty, splendor and scale. When they were occupied by royalty, Korea’s royal palaces were adorned with only the finest works of art and craft produced by the most talented artisans of the times. Those works of art included colorful silk flowers, or gungjung chaehwa.

Written by

Todd Sample,

contributing writer

Photo Courtesy of

Korean Palace Flower

Museum

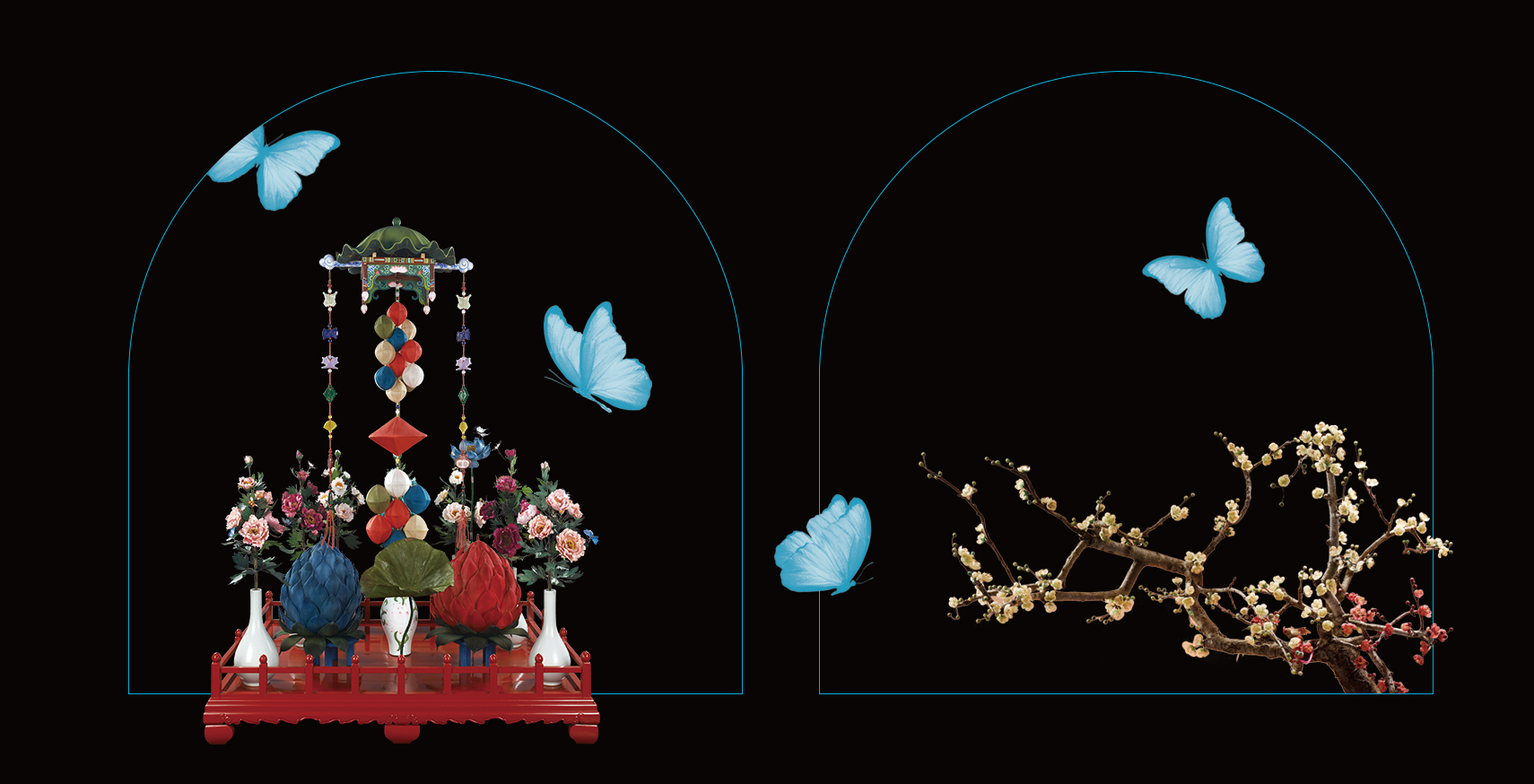

In addition to the normal amount of pomp and circumstance which colored the goings on of the royal court on any given day, the opulence of a royal palace during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) was most evident when events and ceremonies were held and special guests from outside the palace walls were invited within. Of course, flowers were important for adding an extra touch of extravagance to occasions such as banquets and ceremonial rituals. Despite an abundance of flowers growing within the palace grounds, however, in the royal court of the Joseon Dynasty, it was forbidden to cut and decorate the interior of the palace with them out of respect for the royal family’s ancestors who placed value even on a single blade of grass. Instead, artisans of the royal court painstakingly handcrafted elegant arrangements of flowers from silk, ramie, and beeswax, and then dyed them with natural hues to ensure as realistic a representation of the real thing as possible.

This art of royal silk flower making, known as gungjung chaehwa in Korean, replicated flowers as symbols of lasting peace for the state, as well as the health and longevity of the royal family. These elaborate flower arrangements took on different forms depending on the nature of the event. For example, an arrangement called sanghwa (床花) was placed atop the table at banquets held at the palace. Junhwa refers to a large-scale silk flower arrangement decorated with more than 2,000 flowers in addition to silk cranes, peacocks, and even phoenixes nestled among the flowers and stems.

Not only were gungjung chaehwa used to decorate the table or rooms in the palace on auspicious days; they could also be worn. Jamhwa was just one example of wearable silk flowers that were attached to the hat of the king on special occasions like New Year’s Day or on a birthday which began a new decade of life. Common flowers replicated in gungjung chaehwa included plum blossoms, lotus flowers, and apricot blossoms. Depending on the importance of the ceremony, the number of bunches of flowers created could number over 5,000 for just one event. Sadly, this unique tradition of silk flower making was practically lost during the Japanese colonial period when the royal family’s status was stripped and few formal events were held. The appeal of artificial flowers was then lost and replaced by real flowers.

Today, there are still several artisans pursuing this craft, one of which is gungjung chaehwa master Hwang Suro. Her interest in the art of artificial flowers grew upon seeing some at her grandparents’ house while growing up. In fact, Hwang’s maternal grandfather had actually served in the Joseon royal court and thus had firsthand knowledge of palace ceremonies and rituals. Hwang began researching and learning about this traditional craft from Joseon court records and after decades of practice, was eventually designated as National Intangible Cultural Property No. 124 in 2013 due to her efforts to keep this tradition alive. According to Master Hwang, a balance of the four separate characteristics—light, shape, color, and scent—are what constitute a successful example of gungjung chaehwa, the most important of which being color. Considering that the dyes are taken from nature, the amount of time and devotion required to complete one example is longer than expected. As subtle differences in color result in the creation of different flowers, it can take up to a year to make larger arrangements because it is necessary to shape the flowers, dye and then trim them, and repeat the process of tying them with silk thread while waiting for the wrinkles to look more natural. Imagine that in one three-meter-tall flower arrangement, there can be up to 20,000 flowers! Each flower can have a different expression depending on the degree that the flowers “bloom.” At last, the leaves are coated with beeswax after it has been boiled and a scent applied to add fragrance. Those interested in getting a close-up view of royal silk flowers from the Joseon Dynasty can visit the recently established Korean Palace Flower Museum in Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do Province.