June 2021

June 2021

Modernity constitutes the vast majority of items in our daily lives being manufactured with scarcely a human touch. Despite how convenience prevails, people producing objects of beauty with the spirit of a master ‘jang-in jeongshin’ remain. In this piece, we uncover the art of master craftsman Yoon Gyu-Sang, whose paper umbrellas beget him the status of Korea’s singular Intangible Cultural Asset for his art.

Written by

Todd Sample,

contributing writer

Photo Courtesy of

Yoon Gyu-Sang,

Intangible Cultural Asset of

Jeollabuk-do Province

It is an understatement that Korea today is at the crossroads of new and old. On one hand, the country has deservedly earned her reputation as one of the world’s most modern. Innovative technology is actively used — with widespread proficiency — on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, whether it be a centuries-old temple nested amid mountainsides, a palace smack in the center of Seoul, or a park frequented by grey-haired seniors enjoying the company of one another, one is never too far from a window into Korea’s past.

As the country has leapt headfirst into modernity following the Korean War and during subsequent decades of ultra-industrial and economic development, Korea tried to keep its past in the rearview mirror while striving to move ahead. Koreans have adopted this attitude to antiques as well.

Whereas a common weekend activity for Westerners may consist of visiting antique shops, garage sales or flea markets in search of furniture or knick knacks from bygone days, Korea’s post-war race to establish global stature placed more value on the newest and latest, rather than the old or traditional. For instance, a Korean passing by a beautiful antique wooden chest on display at an antique market once remarked, “Why do people pay for that? We had them in our homes when we were poor.”

More recently, however, in light of the growing sentiment that perhaps Korea’s development has come about too quickly at the expense of losing unique aspects of the country’s past and the skill sets that created them, Korea has thankfully experienced a resurgence of interest in antiquated items.

Prior to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic when international tourists still filled the streets of Seoul, Hanbok-clad foreigners were easy to spot along the streets and alleys of northern Seoul. Upon recognizing the appeal of the nation’s traditional national costume among foreign visitors, young Koreans soon began to reconsider the aesthetic beauty of their traditional attire and started donning Hanbok with their friends without embarrassment or irony.

A stark reality of modern society is that the vast majority of the products we use on a daily basis are manufactured nearly or entirely without human touch. Craftsmanship has been usurped in favor of convenience. Thankfully, however, there remain people who produce objects of beauty with the spirit of a master craftsman, a spirit called jang-in jeongshin in Korean. Long before the concept of getting things done ppalli ppalli or “quickly quickly,” sufficient time was taken to produce high quality and delicate items one at a time. One such Korean craftsman is Yoon Gyu-Sang, master of ornate paper umbrellas made on fragile bamboo frames.

Use of paper umbrellas began in China in the 1930s and in the 1950s in Korea, primarily among Korea’s upper crust. For master craftsmen like Yoon, who was born in Jeonju in 1941, the heyday of these umbrellas meant he faced no shortage of work early on in his career. Made by carefully stitching Hanji (traditional mulberry paper) to bamboo spokes, these umbrellas required patience and a steady hand.

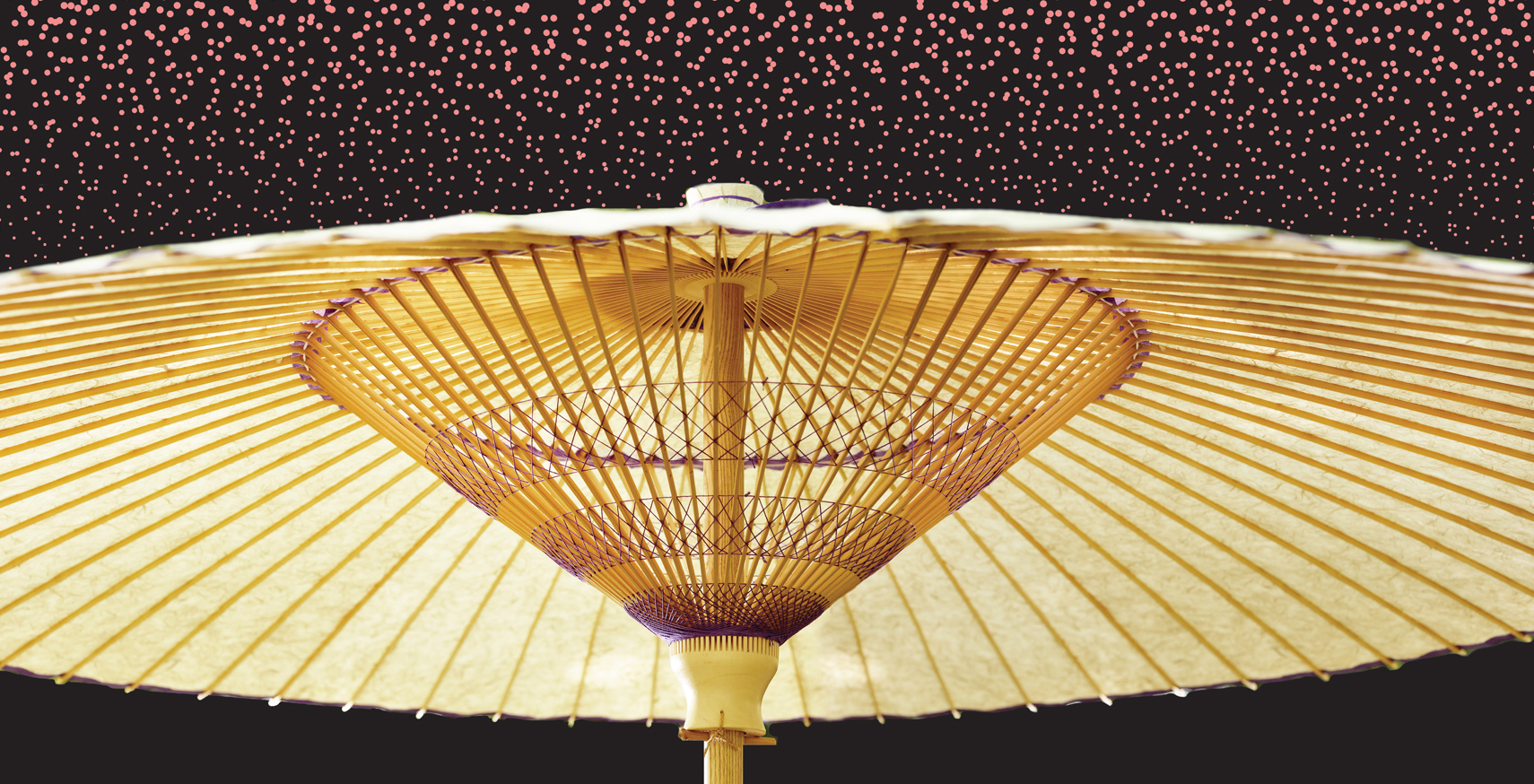

Although breathtakingly beautiful in their completed form, the separate components of these traditional umbrellas must be appreciated on their own, as well. First of all, the bamboo frame of the umbrella is a work of art in its own right. Hand-carved and shaped from bamboo, the spokes of the umbrella are both light and supple, yet at the same time, strong despite their length. In fact, some of the largest jiusan — made primarily for decorative purposes — created by master artisan Yoon have a radius of over 1 meter, while the more complex jiusan can have up to 80 spokes! For both small umbrellas and large ones, as well, the intricacy of the bamboo mechanism used to attach the canopy to the pole itself is a sight in itself to behold.

Despite the relative strength of hanj compared to other types of paper, the mulberry fibers which are used to make this traditional Korean paper are easily visible to the eye, it would seem implausible that an umbrella made to block the rain effectively could be made from paper. Thus, the jiusan made by master craftsman Yoon are coated with either perilla or soy oil and then dried for weeks to make them water resistant. As is also the case with another Korean tradition which utilizes bamboo and Hanji, namely the buchae, or paper fan, designs or calligraphy can be applied to jiusan in order to make them even more ornate, artistic, and unique.

From the late 1950s to the early 1960s, the growth of paper umbrella production meant that by the 1960s, there were more than 30 factories producing them in Jeonju alone.

Sadly, however, the advent of vinyl umbrellas in the 1970s resulted in a drop in demand for paper paper umbrella makers like Yoon, a life of poverty and work in other fields ensued.

It was in 2005 that Yoon made the decision to return once again to the craft. This turned out to be a wise decision as later in 2011, Yoon was designated an Intangible Cultural Asset by Jeollabuk-do Province. Today, he remains the only surviving paper umbrella maker in Korea. His umbrellas and parasols have been featured in art exhibitions and fashion shows and now can cost hundreds of thousands of Korean won if not more.

In spite of the undeniable preference of consumers nowadays for new, cheap, and disposable products, thankfully there is also a growing appreciation among an expanding segment of the market for handmade craftsmanship and preservation of tradition. Although it may be a stretch to imagine modern Koreans strolling down the street with traditional paper umbrellas in hand, repurposing these treasures as decorations for the interior of one’s home or shop, for example, can add a touch of the past to new surroundings and result in a rediscovered relevance for some of the country’s slowly disappearing craft tradition. After all, recognition of such artisan traditions both by the market and official organizations alike increases the likelihood that the appeal of traditional craftsmanship and the beautiful items which result will carry on indefinitely.