March 2021

March 2021

Twenty years have passed since K-pop took off in the late 1990s, but a grand plan for K-pop was already in the works a decade ago. That plan goes beyond the simple export model of broadcasting Korean music abroad and instead, broadens the concept of K-pop by recruiting local talent overseas and integrating them into Korean music groups. The countries targeted at the time were China, by far the biggest market, and Japan, a relatively strategic music production scene.

Written by

Lim Jinmo,

pop columnist

Illustrated by

JB

© YonhapNews

© YonhapNews

Groups launched in the late 2000s and the 2010s — such as f(x) and EXO on the SM label; Miss A, 2PM, and Twice on the JYP label; and Fin.K.L on the YG label — contained members from China, Thailand, and Japan. Non-Koreans are also active in more recentgroups active like Tomorrow X Together, Cravity, Treasure (G)I-dle, Iz*One, and Secret Number. Sources in the music industry expect this trend to continue. Amid the explosive rise of K-pop, a virtuous cycle has formed in which foreign members of these groups have been passionately embraced by their fellow nationals, creating success that has further spurred labels to recruit more foreign members.

This shift from first stage (overseas exports) to second stage (mixed groups of Koreans and non-Koreans) was not the end of the story. A third stage quickly ensued: applying K-pop’s outstanding training and production systems to directly select and develop overseas talent. One prime example comes from JYP Entertainment, led by eponymous producer Park Jin-young. Twice, one of JYP’s biggest acts, includes three members from Japan (Sana, Momo, and Mina) and one from Taiwan (Tzuyu), which makes four of the girl group’s seven members non-Korean.

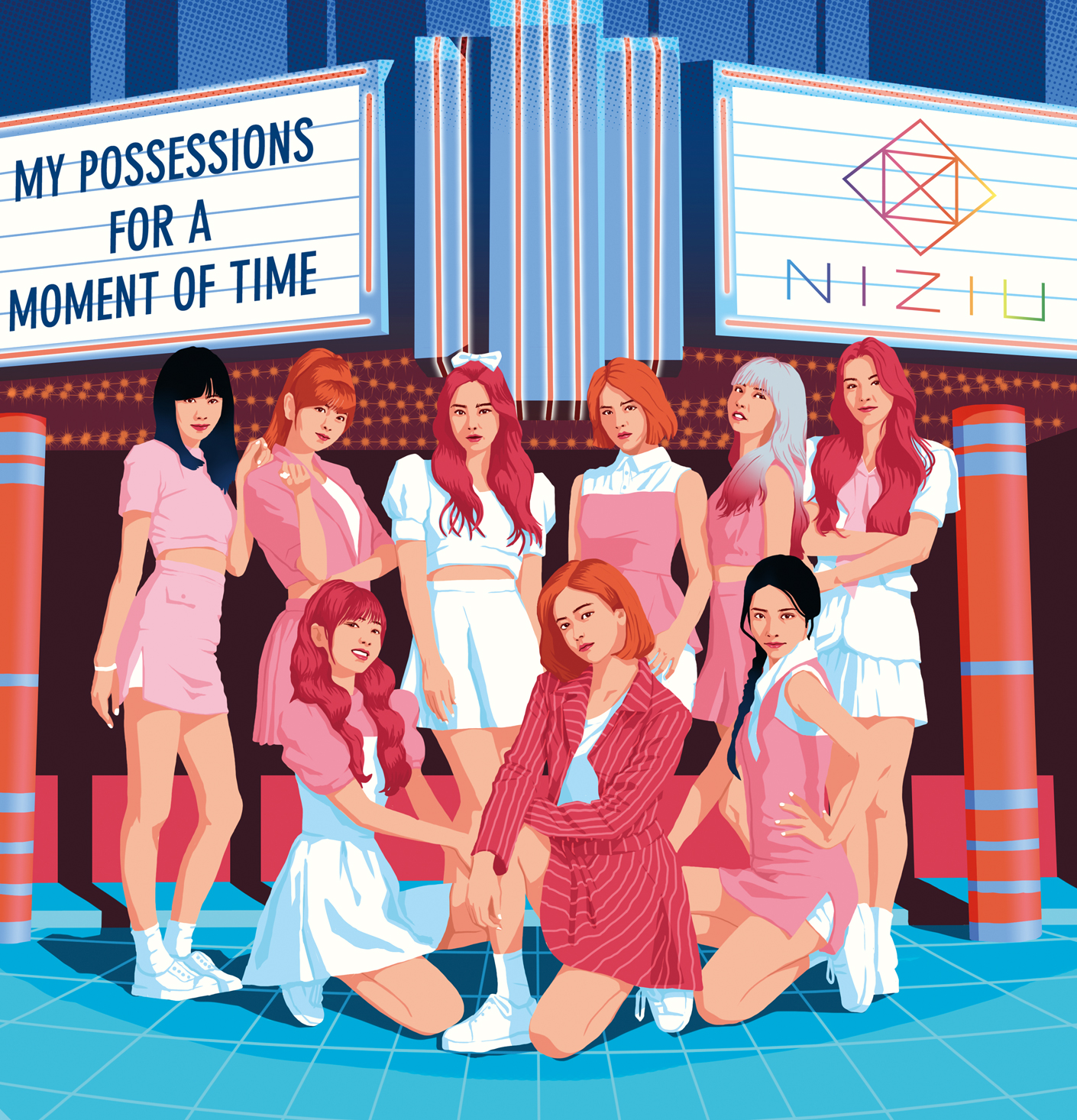

Rather than rest on the laurels of Twice’s enormous success, Park’s label is doubling down on the third stage. JYP partnered with Sony Music Entertainment to hold a Japanese music audition show called the Nizi Project and then combined nine winners into a group called NiziU: a Korean-made Japanese K-pop girl group. NiziU’s first single “Make You Happy” stormed the charts upon its release in 2020, racking up 100 million streams, a first for a female music act in Japan.

They were fostered through similar

strat egies include 2NE1, 4minute

and recent equivalents.

NiziU took part in “Kohaku Uta Gassen,” a New Year’s Eve singing contest that’s a yardstick of genuine popularity in Japan. The group now launches a new project funded by the SoftBank Group, Japan’s biggest telecommunications firm and owner of its local professional baseball team. NiziU leaves no doubt that they’re a product of JYP’s localization, acknowledging that they’ve built their performances on advice from Park Jin-young. The big dreams of entertainment companies hoping to expand into the global market are one factor behind K-pop localization, but the strategy must also be backed by the desire of fans in various countries for K-pop idols of their own. Both factors need to be in place for this strategy to be feasible.

JYP has had this kind of experience before. In 2018, it partnered with China’s Tencent Music Entertainment to launch Boy Story, a group of six teenage boys, all of them Chinese. Boy Story got off to an impressive start that seemed to meet expectations. When the group broadcast a concert online in May 2020 (the first such concert for a Chinese idol group), 5.54 million people tuned in — even more views than BTS got. That could be chalked up to the power of China, but no one would deny that JYP’s technical knowhow was a driving factor.

© YonhapNews

© YonhapNews

SM Entertainment, one of South Korea’s leading labels, was the first both to conceive and execute the third stage of K-pop. Lee Soo-man, SM’s chief producer, had proposed basing Hallyu’s third stage of development on what he called “cultural technology.” Then in January 2016, SM announced the arrival of that third stage when it unveiled NCT. Standing for “new culture technology,” NCT describes a unique system of selecting group members from cities around the world, with no restrictions on the number of recruits, and debuting a series of localized sub-units.

NCT’s catchphrases are “unlimited openness and expansion.” Four sub-units have debuted NCT: NCT 127, which is based in Seoul; NCT Dream composed of teenagers; NCT U, a rotating group of switching members per song; and WayV, which joined in 2020. More sub-units are expected in the future. All 23 NCT members collaborated on the album “NCT Resonance Pt. 1”, which was positively received upon its release last October.

WayV operates under Label V, a joint venture between SM and a Chinese company. SM has also started gearing up for the U.S. market, which is regarded as the most formidable localization challenge.

The ultimate goal of major Korean entertainment companies may be the establishment of a U.S. branch. SM set up its first overseas joint venture SM True in Thailand (2011); the label is ultimately due to pursue a U.S. expansion. Likewise, the label behind BTS, Big Hit Entertainment recently opened its first overseas branch, in Japan. The establishment of Big Hit Japan is part of the label’s plan to identify and train not only locals to perform at home but also artists of global potential.

Big Hit Japan’s first production will be a multinational group consisting of five people eliminated from the I-Land audition show that aired on Mnet in 2020. The group will be backed by sound director Soma Genda, composer Ryosuke Imai and performance director Sakura Inoue, all from Japan, as well as star Korean producer Pdogg.

The localization strategy is ideal for companies that need to cater to local tastes. While K-pop currently garners sensational amounts of attentionglobally, sustaining it will require labels to step up localization efforts, many say. The sooner that can be done, the better.

That’s also the best way to scoop up resources and talent from countries around the world in order to broaden K-pop’s horizons. From its very conception, after all, the term “K-pop” has connoted global scope and status. That fits with the campaign to spread Korean culture worldwide, while also giving Koreans plenty to feel proud about. Through the localization strategy, K-pop at last proves itself worthy of the name.