STORY

Underrated Anniversary

100 Years of Modern Literature

2020 is a year of major milestones, as this year marks the 40th anniversary of the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement, the 60th anniversary of the April 19 Revolution and the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War.

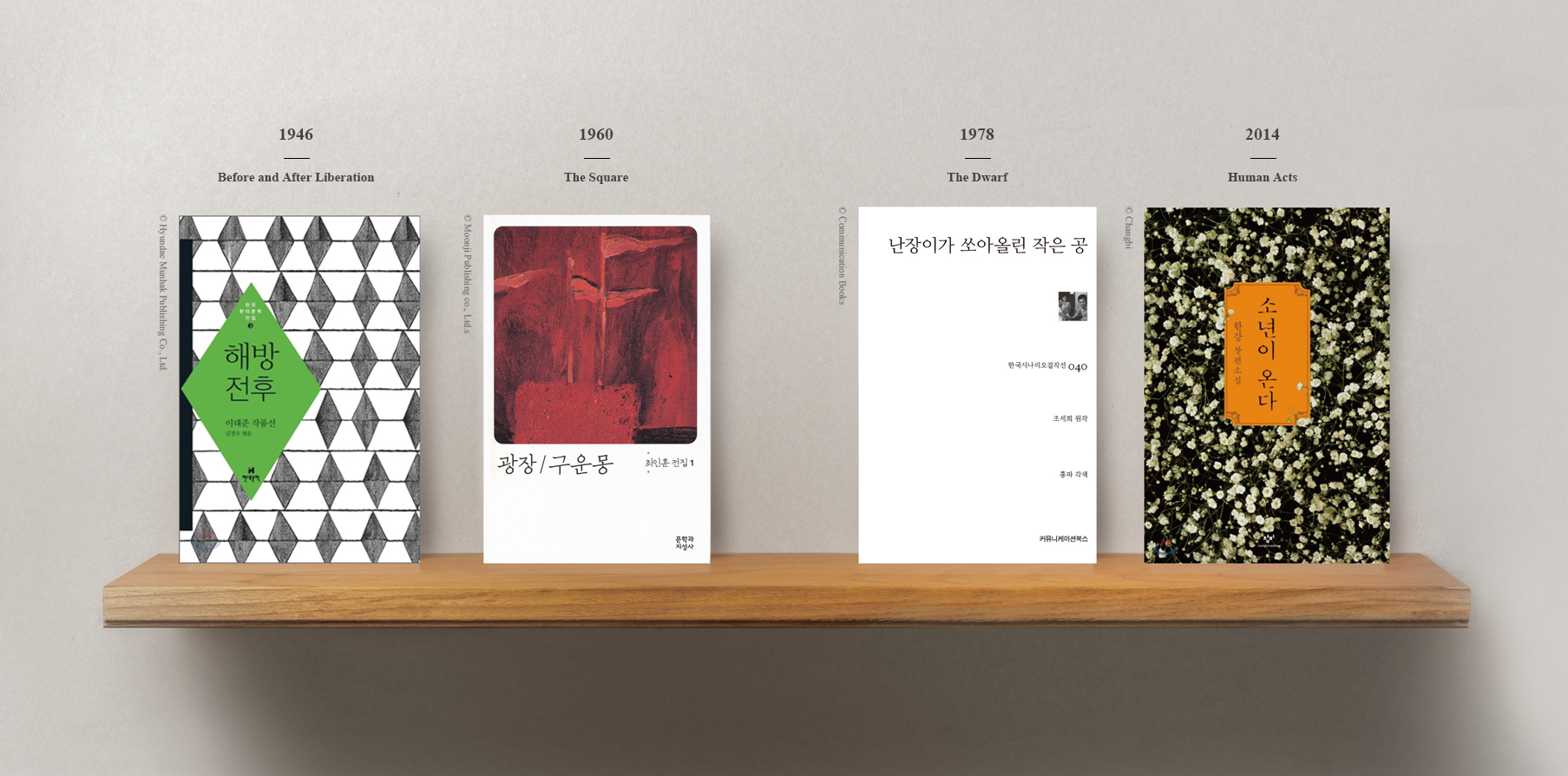

Far less known is that modern Korean literature celebrates its centenary this year. This article takes a look at four key works that reflect not only the excellence of such writings, but also the turbulent incidents occurring at the time.

Written by• Choi Jae-bong,

Literature correspondent at Hankyoreh

Five years before the Korean War, on Aug. 15, 1945, Korea finally found liberation after being stripped of its sovereignty by imperial Japan. The 35 years of Japanese rule saw Koreans robbed of their land and food and forced into slavery of both labor and sex. Despite being denied basic human rights and national dignity, the Korean people gleaned steadfast hope from their modern literature.

Dreams of Liberation

Published a year after Korea gained independence from Japanese colonial rule, Lee Tae-Jun’s novella “Before and After Liberation” vividly depicts what preceded and followed the 1945 liberation through the eyes of the protagonist Hyun. After being harassed by Japanese colonial police, he takes temporary shelter on the rural outskirts of Gangwon-do Province. There, he meets an archaic scholar and former Confucian schoolteacher dubbed “Employee Kim.” They discuss the woes of losing their country’s sovereignty until the long-awaited liberation takes Hyun back to Seoul. In a liberated Korea, he harbors writing aspirations and joins a new literary organization. When Employee Kim travels from his rural whereabouts to find Hyun, the former is wary of the organization’s cooperation with the left and frets that Hyun is a communist. The ending scene’s contrast between Hyun’s literati acquaintances “buzzing with energy in their preparation for the National Literati Contest” and Employee Kim’s “outmoded, forlorn silhouette subsiding away” displays the shift from an outdated order to the new.

At Hongkou (now Lu Xun) Park in Shanghai, China, on April 29, 1932, Korean independence activist Yun Bong-gil threw a bomb at the site of the Japanese emperor’s birthday celebration. Police immediately arrested Yun. © YonhapNews

Ideological Division

The joy of liberation collapsed just five years later with the tragedy of national division caused by the 1950-53 Korean War. The war was both a proxy conflict between capitalist and communist ideologies and a violent backlash incurred by accumulated and suppressed social inequalities on the Korean Peninsula.

Published in 1960, Choi In-hun’s novel “The Square” depicts the tragedies of war and longing for utopia through the youthful protagonist Lee Myung-joon. Despite being in hiding as a university student in the South, Lee is exposed through mention of his father, a resident of the peninsula’s northern half, by a North-to-South broadcast. Lee is taken to a police station and beaten. Disillusioned by the reality in the South, he escapes to the North in the hope of finding egalitarianism, but fails to. When civil war breaks out, he joins the Korean People’s Army of the North, loses his lover and becomes a prisoner of war. After being freed after the conflict ends, he chooses neither North nor South Korea and opts to head toward neutral territory instead. On a ship to India, he jumps into the ocean, an act representing his failure to find proper execution of ideologies professed by either side of the peninsula, whether the communist North’s egalitarianism or the capitalist South’s libertarianism. Lee’s suicide simultaneously expresses lament at this misfortune and evokes a yearning for a utopia where ideology and reality are in harmony.

Patrols stand guard at the Military Demarcation Line. © YonhapNews

Wishing for Utopia

Cho Se-hui’s “The Dwarf,” a short story collection published in 1978, depicts the harsh lives of laborers and poverty-stricken suburban residents who suffered during national industrialization and economic growth. At the fictional and paradoxically tragicomic address of Seoul Nakwon-gu, Haengbok-dong (“Nakwon” is a transliteration of the Korean word for “paradise” and “haengbok” means “happiness”), a dwarf’s family is forced to move out of Seoul and relocate to Eungang, a seaside factory zone. The dwarf kills himself by jumping off a roof as his last act of defiance against discrimination and injustice. His children, who are worked to the bone at Eungang factories in being exploited for their labor and denied basic human rights, are driven to trying to murder their boss as an expression of resistance.

The dwarf and his children ultimately face defeat in this novel, but their sacrifices and spirit of resistance are not in vain. After the dwarf dies, his son remembers the world his father envisioned, saying, “In the world of Father’s dreams, everyone had work, received compensation that covered sustenance and proper education for their kids. In that world, where neighbors treat each other with love and respect, the rulers neither lead nor pursue extravagant lifestyles. They, too, were entitled to the exposure and knowledge of human pain.”

“Human Acts”

Laborers at a Korean factory in 1983 use machinery. © YonhapNews

The brutal suppression of a civilian movement in Gwangju from May 18-27, 1980, and the movement itself epitomized the military dictatorship of President Park Chung-hee, who ruled Korea from 1961-79.

In 2014, two years prior to releasing her globally acclaimed novel “The Vegetarian,” author Han Kang published “Human Acts,” which centers on the murder of a boy, Dong-ho, by soldiers. Through his surviving acquaintances and his mother, the novel depicts scenes of brutality unsettling for readers. What led Han to write the book and why is it a worthy read? A censored passage provides a hint: “What does it mean to be human? What should we humans do in order not to forgo our humanity?”

Responses to this question can be gleaned from what probably drove the relentless spirit of the participants in the May 18 movement as well as those in the Candlelight Revolution of 2016-17 at Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Plaza. As such, modern Korean literature over the past century has refused to ignore historical events essential to national identity. By recording such critical moments in the country’s history, such writings continue to serve as a source of consolation and condolences for the Korean people.