Contents

Historic Anniversary · Written by Jeon Han Illustrated by Manus Eugene Photo courtesy of The Independence Hall of Korea

Human Rights Lawyer

¡®Who Listened to

His Own Conscience¡¯

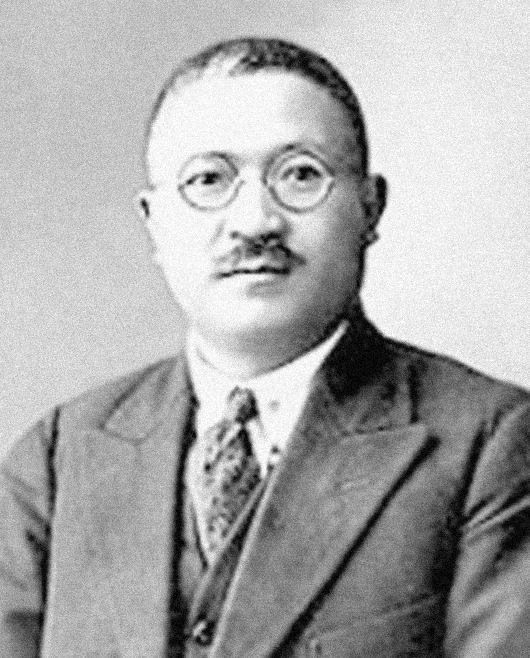

Tatsuji Fuse

Tatsuji Fuse, a Japanese lawyer who listened to the ¡°voice of his own conscience,¡± chose to lead a life

guided by principle. This led him to defend Koreans active in the independence movement and inform

about Japan¡¯s wrongful and unjustifiable plunder of Korea to the world. Standing by the weak in society

regardless of the opinions of and suffering caused by others, he was nothing short of a paragon of

righteousness and justice during this tumultuous period.

Together with the people to live, for the people who must die (ß檪٪¯ªóªÐÚÅñëªÈÍìªË, Þݪ¹ªÙª¯ªóªÐÚÅñëªÎ?ªË).¡± This phrase is inscribed on the tombstone of Tatsuji Fuse (øÖã¿òãö½, 1880-1953), the first Japanese recognized by the Korean government as a person of merit in the fight for Korean independence. He was posthumously honored in 2004 with the Aejokjang (Independence Medal) of the Order of Merit for National Foundation. His tombstone, called Hyeonchangbi, is located at Akebono Minimi Park in his Japanese hometown of Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture, and symbolizes his lifelong devotion to the ¡°people.¡±

In his early days, Fuse studied Gyeomae Sasang (ÌÂäñÞÖßÌ), or the philosophy of universal love preached by the ancient Chinese sage Mozi (Ùøí) based on the teaching ¡°Love for all of mankind comes from heaven and is the legitimate, moral duty given to the people.¡± As he grew into a young man, Fuse extensively read the works of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy.

National Foundation (National Medal grade), which he received posthumously in 2004.

From Prosecutor to Human Rights Lawyer

Holding Mozi¡¯s philosophy and Tolstoy¡¯s literature dear to his heart, Fuse graduated from the School of Law at Meiji University in 1902. In the same year, he was appointed a public prosecutor at the Utsunomiya District Court in starting a path that guaranteed success in Japanese society at the time. Yet one event caused him to head toward another direction.

Fuse was tasked with indicting a woman who had tried to commit suicide with her child, but ended up surviving while her offspring died. This incident made him question the adequacy of the social system and enforcement of laws.

Thinking that his own conscience must guide his life, he quit his job as a prosecutor after just six months to become a human rights lawyer.

Opening a law firm in Tokyo, Fuse began making a name for himself and enjoyed a decade of recognition as a sought-after lawyer. In 1911, a year after Korea was forced by Japan to sign an annexation treaty, he published the paper ¡°Paying My Respects to Joseon¡¯s (Korea¡¯s) Independence Movement¡± that defined the Japanese annexation of the Korean Peninsula as ¡°an invasion¡± and discussed Joseon¡¯s ¡°righteous armies¡± formed by the people. His action immediately led to a criminal investigation into him and his name being put on a blacklist.

Despite facing heavy police pressure, Fuse continued to defend society¡¯s weak and the people of Joseon and Taiwan, two countries that Japan had colonized. He eventually defended Choi Pal-yong (1881-1922) and Song Gye-baek (1894-1920), both of whom led in 1919 the Feb. 8 Independence Declaration in Tokyo, a movement led by Korean students abroad. Fuse insisted on the innocence of both activists despite facing a charge of treason from Japanese prosecutors.

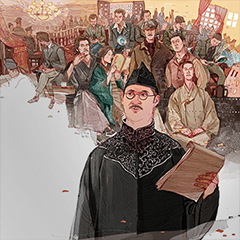

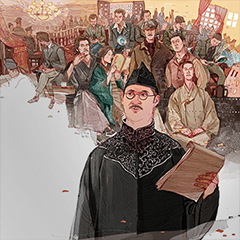

An exhibition in 2016 in Japan introduces Tatsuji Fuse along with Korea¡¯s independence activists.

An exhibition in 2016 in Japan introduces Tatsuji Fuse along with Korea¡¯s independence activists. Tatsuji Fuse is featured in the Korean historical film ¡°Anarchist from Colony,¡± which depicts the life of Park Yeol, a Korean anarchist and freedom fighter whom Fuse defended.

Tatsuji Fuse is featured in the Korean historical film ¡°Anarchist from Colony,¡± which depicts the life of Park Yeol, a Korean anarchist and freedom fighter whom Fuse defended.¡®Following His Conscience¡¯

In 1920, Fuse, then in his 40s, announced that he would leave the legal profession to help society, declaring his ¡°Confession of Self-Revolution.¡±

His confession stated, ¡°A person must listen to his or her own genuine voice that explains the life that he or she should live (ìÑÊàâÁªÇªâªÉªÎªèª¦ªÊßæªÛ°ªòª¹ªëªÎª¬ªèª¤ª«ªËªÄª¤ªÆ¡¢ïáòÁªÊí»ÝªÎ?ªòÚ¤ª«ªÊª±ªìªÐªÊªéªÊª¤¡£)... this is the voice of conscience, and thus, I solemnly declare a ¡®self-revolution¡¯ (ª³ªìªÏÕÞãýªÎ?ªÇª¢ªë¡£ÞçªÏª½ªÎ?ªË?ªÃªÆ??ªË¡ºí»ÐùúÔÙ¤¡»ªòà¾å몹ªë¡£).¡±

In 1923, when Kim Si-hyeon and other members of the pro-Korean independence group Euiyeoldan (Heroic Corps) were arrested for trying to bomb the headquarters of the Japanese Government-General in Korea, Fuse took up their case to ensure a fair verdict. In the same year, he criticized Japan¡¯s martial law command and police for massacring thousands of ethnic Koreans after the Great Kantõ Earthquake; the victims were blamed for the quake. He also sent a letter to the Korean dailies Dong-A Ilbo and Chosun Ilbo to apologize as a Japanese.

This photo shows Tatsuji Fuse wearing a Hanbok (traditional Korean attire) and a gat (hat).

Fuse also represented Pak Yeol (1902-74) and his wife Fumiko Kaneko (1903-26, ÑÑíÙþí), an independence fighter couple who planned to assassinate the Japanese emperor. The lawyer claimed their innocence in a case that received national attention in Japan, and also carried out the necessary work to allow getting married behind bars. After Kaneko died in prison under suspicious circumstances, Fuse buried her remains in Pak¡¯s hometown of Mungyeong, Gyeongsangbuk-do Province.

In 1932, Fuse had his lawyer¡¯s license revoked due to his strong criticism of the Japanese government¡¯s authority; he spent time in prison for violating the press law in 1933 and a law on the maintenance of public order in 1939. Eventually, he regained his license in 1945 just after Japan¡¯s surrender during World War II.

In 1946, the human rights activist wrote a draft of the Joseon Constitution for National Foundation for a liberated Korea and also the biography ¡°Victor of Destiny, Pak Yeol¡± about the freedom fighter whom he had defended. The book was later made into a Korean film in 2017 named ¡°Anarchist from Colony.¡±

Other Articles