In November 1916, Frank W. Schofield arrived in Korea from Canada to perform missionary work, and got to learn more about the country and its people while lecturing on bacteriology at Severance Union Medical College in Seoul. He then started seeing how Koreans were suffering under Japanese colonial rule.

Korean freedom fighter Lee Gap-seong informed Schofield the day before March 1, 1919, that an independence movement and a ceremony for a declaration of independence would occur. The doctor was also asked to translate into English and deliver a copy of the declaration to the White House.

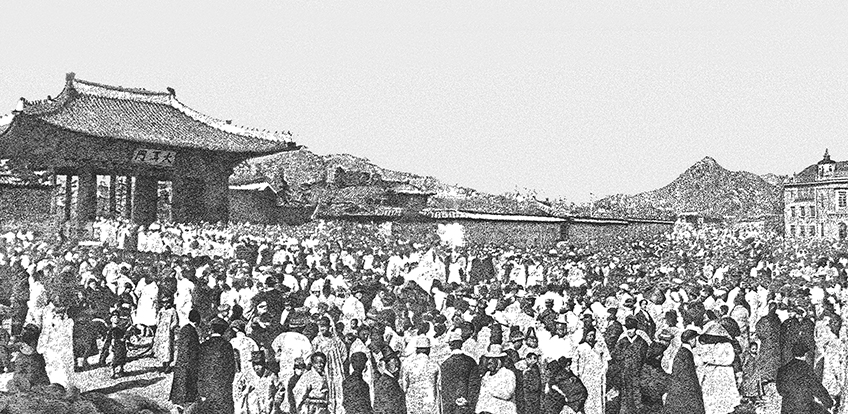

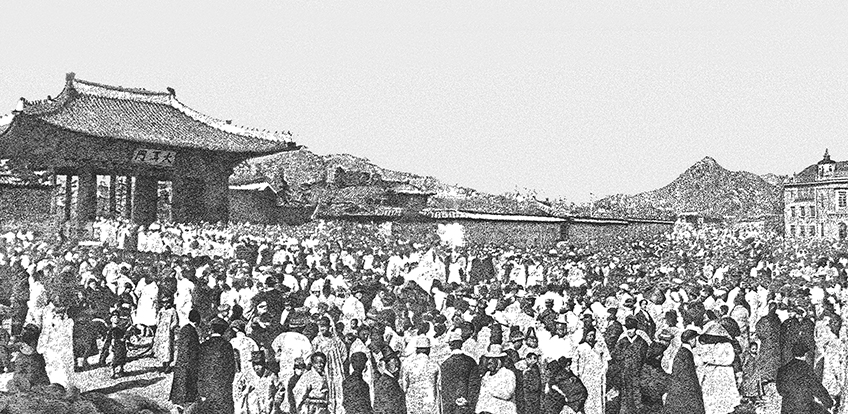

Lee visited Schofield again the next morning and asked him to take pictures of a massive student protest at 2 p.m. in Tapgol Park. Schofield made his way to the park and captured the historic moment where the crowd cried “Manse (Hurrah), Korean independence!” He followed the crowd to Jonggak, Gwanghwamun Gate and Daehanmun Gate of Deoksugung Palace. His arm and leg were affected by polio but he went up the hill across Daehanmun Gate and took pictures there. His photos provided vivid and crucial images of the historical day.

Schofield also reported on the Jeam-ri Massacre, in which Japanese soldiers herded residents into a church in the village of Jeam-ri in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi-do Province, shot them and set fire to the building in retaliation for the independence movement. A combined 23 people were killed in the incident, including two mothers.

Upon hearing this news on April 17, Schofield immediately visited the scene. His report “The Massacre of Chai-Amm-Ni” was posted on the English-language newspaper Shanghai Gazette on May 27, 1919. Around that time, another report headlined “Report of the Su-chon Atrocities” was issued on July 26, 1919, in the American magazine Presbyterian Witness.

A photo of the March First Independence Movement taken by Frank W. Schofield © The Independence Hall Of Korea

No Reservations

After Japan took over the Korean Peninsula, Japanese soldiers kept a close watch on everyone. Thus it was far from easy, even for foreigners, to help the Korean independence movement. Openly criticizing the Japanese colonial government or resisting could put anyone’s life at risk.

Schofield, however, never hesitated in helping Korea’s independence movement. In May 1919, he sent a scathing letter to Seoul Press, a media outlet representing the Japanese colonial government, blasting a favorable article it published about Seodaemun Prison, which was notorious for torturing independence fighters. He visited the prison to meet activists Roh Gyoung-soon, a nurse at Severance Hospital, Yu Gwan-soon and Eo Yoon-hee.

The Canadian doctor witnessed the prison’s brutal conditions and heard from Lee Ae-joo, who was hospitalized at Severance Hospital, of abuses there such as mistreatment and torture. In talks with Hasegawa Yoshimichi, the Japanese governor-general of Korea, he urged improvement of the prison’s conditions and an immediate stop to torture there.

The exhibition “Korea’s Independence Movement and Canadians” is held at the City Gallery of Seoul Citizens Hall. © Jeon Han, Korea.net

Afterwards, Schofield devoted himself to covering and publicizing Japan’s atrocities to the world. His writings and pictures were published on media including The Korean Situation by the U.S. Christian Coalition, The Independence Newspaper by the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai and The Korean Independence Movement, an English-language photo journal. His pictures were also attached to a report sent to the U.S. secretary of state on July 17, 1919.

Schofield also went to Japan in August 1919 and gave a speech criticizing Japan’s atrocities in front of a crowd of 800 missionaries. In a meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Hara Takashi that the latter wrote about in his journal entry dated Aug. 29, 1919, the doctor urged Tokyo to stop its inhumanity.

The Canadian’s proactive actions made Japan uncomfortable. A report from the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church in Canada said, “Japanese cops obviously hated Schofield’s reports and articles unveiling the torture, violence and brutality the Japanese inflicted on Koreans, which explains why they attacked Schofield. One governor is said to have called him ‘a cunning conspirer and dangerous figure.’”

In 1958, the Korean government invited Frank W. Schofield as a state guest and expressed gratitude for his contributions to the March First Independence Movement. © National Archives of Korea

Preserving Spirit of Independence Movement

Even after Schofield returned to Canada in 1920, he expressed his attachment and love for Korea on Christmas cards sent in 1926 and 1931, saying, “Korea is my home. I think I am a man of Joseon (Korea) rather than Canada.”

He also loved to be called Seok Ho-pil, a Korean version of his surname. Even after the country achieved independence, he dedicated his life to spreading and preserving the spirit of the March First Independence Movement.

When he did return to Korea in 1958, he wrote articles encouraging Koreans to continue the spirit of the movement such as “March First, 1919 and March First, 1963 (1963),” “What Happened on March 1, 1919? (1966),” “‘Hurrah! Independence!’ That United All (1969)” and “The March First Independence Movement Is the Symbol of the Korean Spirit (1969).”

His fond affection for Koreans can be also found in the last article he wrote for The Chosun Ilbo on March 1, 1970, a little more than a month before his death. He said, “Don’t forget how the young and old sacrificed in 1919 for Korea’s future. These are a few words I want to tell young Koreans today. At times, we face injustice we have to fight against and sometimes the price for achieving that goal is our life. This, however, sets us free from a state of slavery and brings us a bright future.”